We miss Bap Kennedy. There was a tone in his music that will not be replaced. It was an authentic part of the man and there was a grain in his voice that related like Hank Williams, Townes Van Zandt or Gram Parsons. Fathoms of blues. Untold stories between the cracks in the words. His lyrics hinted at the deeps but he wasn’t inclined to put it all out there. You had to trust Bap, and we did.

We miss Bap Kennedy. There was a tone in his music that will not be replaced. It was an authentic part of the man and there was a grain in his voice that related like Hank Williams, Townes Van Zandt or Gram Parsons. Fathoms of blues. Untold stories between the cracks in the words. His lyrics hinted at the deeps but he wasn’t inclined to put it all out there. You had to trust Bap, and we did.

‘Sunrise’ by The Divine Comedy is a song that begins in the murk and ambiguity of Northern Ireland in the Eighties. Neil Hannon puts out the idea that his birthplace, Londonderry is also known as Derry City. His home is Enniskillen but historically it’s about the mythology of Inis Ceithleann, water and land and ancient footfalls. The singer gives his dues to the different narratives and steers a self-conscious path between them. Then on November 8, 1987 the bomb goes off at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday and there is no easy way to walk that line:

‘Sunrise’ by The Divine Comedy is a song that begins in the murk and ambiguity of Northern Ireland in the Eighties. Neil Hannon puts out the idea that his birthplace, Londonderry is also known as Derry City. His home is Enniskillen but historically it’s about the mythology of Inis Ceithleann, water and land and ancient footfalls. The singer gives his dues to the different narratives and steers a self-conscious path between them. Then on November 8, 1987 the bomb goes off at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday and there is no easy way to walk that line:

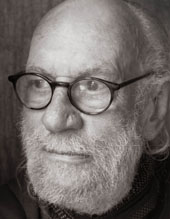

The health is not great and Jackie Flavelle is sore because he can’t load up the gear and go touring with his bass and his comrades in jazz. It’s the life he has known for 60 years. His talk is hepcat jive and north Belfast grit. He cusses often and the eyes are undimmed behind those lenses. Medical procedures will keep him off the road for some time, tethered in Donaghadee. He will be 79 in October. Time to pause a moment and review a substantial life.

The health is not great and Jackie Flavelle is sore because he can’t load up the gear and go touring with his bass and his comrades in jazz. It’s the life he has known for 60 years. His talk is hepcat jive and north Belfast grit. He cusses often and the eyes are undimmed behind those lenses. Medical procedures will keep him off the road for some time, tethered in Donaghadee. He will be 79 in October. Time to pause a moment and review a substantial life.

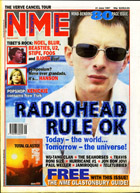

Twenty years ago, NME commissioned me to write a cover story about Radiohead and the release of ‘OK Computer’. It was an exciting ask, and the story would involve a visit to Oxford in late May to meet Colin, Ed and Phil, followed by a trip to New York and a ride with Radiohead in a minivan to the Tibetan Freedom Concert on Randall’s Island. Continue Reading…

Twenty years ago, NME commissioned me to write a cover story about Radiohead and the release of ‘OK Computer’. It was an exciting ask, and the story would involve a visit to Oxford in late May to meet Colin, Ed and Phil, followed by a trip to New York and a ride with Radiohead in a minivan to the Tibetan Freedom Concert on Randall’s Island. Continue Reading…

He counts the birds and recites the enchanted names of flowers. Michael Longley wows at the whooper swan and parses the natural joys on the Atlantic reach of Carrigskeewaun, County Mayo. In recent years, his poetry collections have seemed prolific, yet they also feel precious and rare. Angel Hill appears just ahead of his 78th birthday and it resounds with themes of family, absent friends, migrations, arrivals and generations at their song.

He counts the birds and recites the enchanted names of flowers. Michael Longley wows at the whooper swan and parses the natural joys on the Atlantic reach of Carrigskeewaun, County Mayo. In recent years, his poetry collections have seemed prolific, yet they also feel precious and rare. Angel Hill appears just ahead of his 78th birthday and it resounds with themes of family, absent friends, migrations, arrivals and generations at their song.

The gull can’t help it. This is the domain of the birds – high up on the Belfast skyline with the cranes and the cathedral, the new builds and the vintage nesting spots. Tonight however marks the start of the Women’s Work programme, and the flat roof of the Oh Yeah building is host to a few dozen humans and a live performer, Katharine Philippa. So the gull swoops and disapproves while a few seabird mates gang up on nearby ridges and flues, all feathered annoyance and minor Hitchcock menace.

The gull can’t help it. This is the domain of the birds – high up on the Belfast skyline with the cranes and the cathedral, the new builds and the vintage nesting spots. Tonight however marks the start of the Women’s Work programme, and the flat roof of the Oh Yeah building is host to a few dozen humans and a live performer, Katharine Philippa. So the gull swoops and disapproves while a few seabird mates gang up on nearby ridges and flues, all feathered annoyance and minor Hitchcock menace.

Mark Rothko is a massive kvetch. He hates Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol. He despises the art dealers and the chattering class of Manhattan that misunderstands his art and would prefer a nice colour for the overmantle.

Mark Rothko is a massive kvetch. He hates Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol. He despises the art dealers and the chattering class of Manhattan that misunderstands his art and would prefer a nice colour for the overmantle.

He scorns the Seagram Corporation that has paid him $35,000 to put a new collection into the Four Seasons restaurant on Park Avenue. They have afforded him scale and status. He wants control over the lighting and the placing of his great canvasses. But already there is stress. Continue Reading…

Touts. What a top mess of noise and sedition, punk and petulance. Tunes that run out of road after a minute and a half – every second screeching with need and urgency. Songs about walls and clampdowns, shameful deals and base electioneering. A realisation that the vision might be compromised and lost in transit. But still there’s a sway in being engaged and inflamed, seeking transcendence in Saturday thrills, in the reckoning of a back alley or in a brute chorus.

Touts. What a top mess of noise and sedition, punk and petulance. Tunes that run out of road after a minute and a half – every second screeching with need and urgency. Songs about walls and clampdowns, shameful deals and base electioneering. A realisation that the vision might be compromised and lost in transit. But still there’s a sway in being engaged and inflamed, seeking transcendence in Saturday thrills, in the reckoning of a back alley or in a brute chorus.

Peadar Ó Riada recently took the road north to Bellaghy, determined to pay tribute to Seamus Heaney. He sat at the piano in the Helicon room of the Heaney Home Place and he gave soul and airs to the poet’s memory. Sometimes he was elegant but on occasion, the notes were awry, loose. It was not about finesse, but he absolutely meant it.

Peadar has achieved much with his music, his arrangements and his guidance of the Cór Chúil Aodha, a male choir from Muskerry, Co. Cork. They sing as Gaeilige in an intense, spiritual manner. The choir was formed in 1964 by Seán Ó Riada, his dad, who brought a radical ear to Irish music in the late Fifties and across the next decade. Seán was only 40 when he died but the legacy was vast. Two weeks before he passed, he asked his son to look after the choir. The boy was 16. Peadar put marks on the keyboard and thus he could manage the chords. He was off.

At the opening of a QFT retrospective on John T. Davis, we see a 20 minute sample of his ongoing film, Mshiikenhmnising. The artist is 70 and he has reprised many of his themes. America is an expanse, a colour field, a challenge and a con job. Like Walt Whitman, he is drawn to the rhythm and the fervour, those haunting chimes of freedom. He connects to this tradition through the beat poets and their outsider prosody. It’s about the groove, the riffology, the swing of it all.

At the opening of a QFT retrospective on John T. Davis, we see a 20 minute sample of his ongoing film, Mshiikenhmnising. The artist is 70 and he has reprised many of his themes. America is an expanse, a colour field, a challenge and a con job. Like Walt Whitman, he is drawn to the rhythm and the fervour, those haunting chimes of freedom. He connects to this tradition through the beat poets and their outsider prosody. It’s about the groove, the riffology, the swing of it all.

Twitter

Twitter