There’s a track on the new Defects album called ‘Chokehold’. It remembers the death of Eric Garner in New York, 2014, a savage moment in the Black Lives Matter story that registered in the music of Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar and many others. The song is horrendously relevant again, a fact that’s no comfort to any artist with a piece of conscience. For the Defects, who came out of the Belfast punk scene 40 years ago with ‘Brutality’, a song about the mishaps at the RUC Castlereagh Holding Centre, it might seem like they’re going over familiar ground. But still they roar and protest, because that’s the spiky prerogative.

There’s a track on the new Defects album called ‘Chokehold’. It remembers the death of Eric Garner in New York, 2014, a savage moment in the Black Lives Matter story that registered in the music of Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar and many others. The song is horrendously relevant again, a fact that’s no comfort to any artist with a piece of conscience. For the Defects, who came out of the Belfast punk scene 40 years ago with ‘Brutality’, a song about the mishaps at the RUC Castlereagh Holding Centre, it might seem like they’re going over familiar ground. But still they roar and protest, because that’s the spiky prerogative.

There was an Irish market for recordings about political opinion and national identity. Two enterprises handled the bulk of the demand: Outlet and Emerald. Neither of them showed an especially partisan hand. They pressed up records from male voice choirs, rebel balladeers, pipers, céilí outfits and Protestant marching bands. By the early 70s, there was an established network that took in record shops and independent retailers but also saw value in street traders and market stalls in Glasgow, Blackpool, Crossmaglen, wherever.

There was an Irish market for recordings about political opinion and national identity. Two enterprises handled the bulk of the demand: Outlet and Emerald. Neither of them showed an especially partisan hand. They pressed up records from male voice choirs, rebel balladeers, pipers, céilí outfits and Protestant marching bands. By the early 70s, there was an established network that took in record shops and independent retailers but also saw value in street traders and market stalls in Glasgow, Blackpool, Crossmaglen, wherever.

The revolution will be visualised. Sodomy will be saved from Ulster. The Tayto Man from the Republic will shake hands with his Cheese & Onion enemy across the border. A big gay rainbow will erupt from the Stormont Assembly. And the special, neglected buildings of Belfast will defy the rapacious developers – glowing with an alternative, civic love.

The revolution will be visualised. Sodomy will be saved from Ulster. The Tayto Man from the Republic will shake hands with his Cheese & Onion enemy across the border. A big gay rainbow will erupt from the Stormont Assembly. And the special, neglected buildings of Belfast will defy the rapacious developers – glowing with an alternative, civic love.

Operation Demetrius was enacted by the British Army on August 9-10 1971 in consultation with the Unionist government of Northern Ireland. This was internment without trial and 342 people were lifted, many in dawn raids. The Army had targeted supposed Republican militants, although Civil Rights figures were also on the list of suspects and several of these names evaded arrest. The accuracy of Army intelligence was later questioned. No Loyalists were interned until 1973. Some Protestants taunted their neighbours with a chant adapted from ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’, the 1971 hit single by Middle of The Road: ‘where’s your daddy gone?’

Operation Demetrius was enacted by the British Army on August 9-10 1971 in consultation with the Unionist government of Northern Ireland. This was internment without trial and 342 people were lifted, many in dawn raids. The Army had targeted supposed Republican militants, although Civil Rights figures were also on the list of suspects and several of these names evaded arrest. The accuracy of Army intelligence was later questioned. No Loyalists were interned until 1973. Some Protestants taunted their neighbours with a chant adapted from ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’, the 1971 hit single by Middle of The Road: ‘where’s your daddy gone?’

Internment was followed by mass displacements in mixed-religion areas such as the Ardoyne. It was reported that 240 houses in Farringdon Gardens, Cranbrook Gardens and Velsheda Park had been set on fire as Protestants left the area. The houses were deliberately burnt to prevent new tenants moving in. Flatbed trucks and lorries were commandeered from Loyalist areas and brought to those streets to aid this evacuation. The fall-out of such actions was that other residents had to flee for their own safety. Thus, the O’Shaughnessey household packed and left at speed when their home on Cranbrook Gardens caught fire:

‘There were tensions simmering for about three days,’ Anthony O’Shaughnessey recalled. ‘People did not know what was going to happen. I thought it was a dream and, in the morning, everything would be okay.’

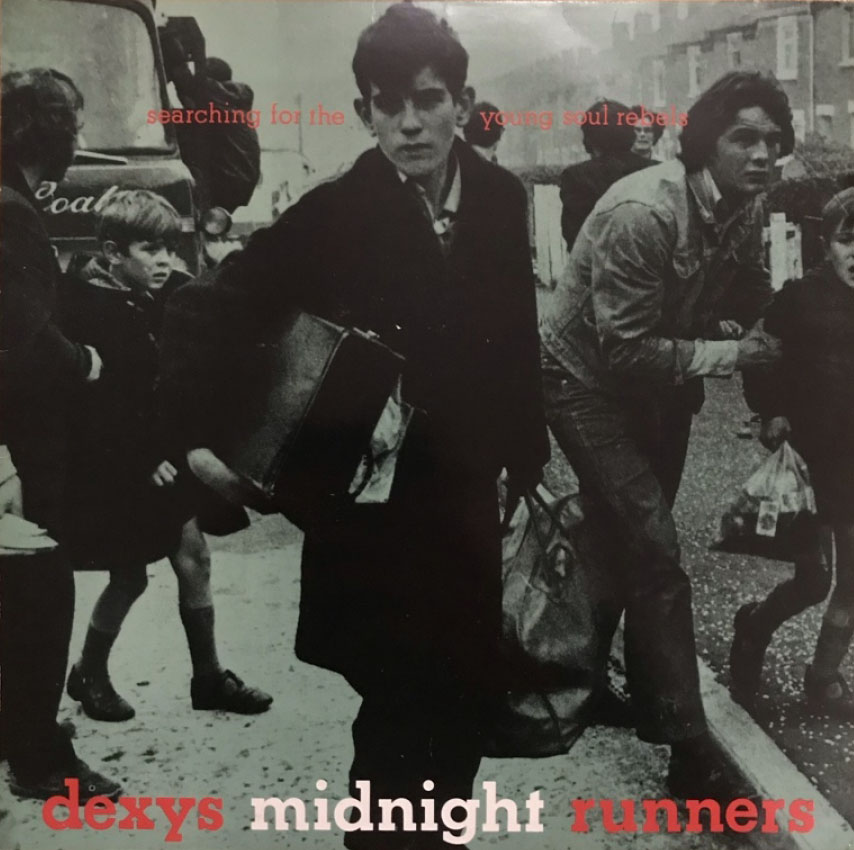

London’s Evening Standard used a photograph of this disturbance. The image shows 13-year-old Anthony with a grip bag in his left hand and a cardboard suitcase under his right arm. He looks at the camera in a distracted manner. His mother Kathleen is in the background and his brother Kevin is at his right elbow, in a duffel coat. On the other side, his brother Gerard is carrying a plastic bag with some personal effects, being led onto the pavement by a man in a Wrangler jacket and jeans. The children are understandably distressed. Behind the boys, a man is clambering on to the back of a coal lorry. Anthony would later remember the immensity of the moment.

‘That day was probably the biggest evacuation since World War II, where so many people retreated into their own communities. The Protestants were evacuated from Ardoyne. Later that night a Loyalist mob from outside the area started burning the houses two streets behind us. Our house caught fire from the houses behind us and burnt to the ground.’

A cropped version of the image was later used as the album cover of the 1980 debut from Dexys Midnight Runners. Anthony had not been aware of the cover until a friend spotted a copy in Smithfield Market. There were several meetings with Kevin Rowland from the band afterwards and bemused quotes from Anthony when vintage marketing posters featuring his image began reaching high prices on the collectors’ market. The unwitting cover star also told reporters that he had come to terms with the trauma, that he had no desire to return to his old neighbourhood: ‘I don’t think I would like to live in a shared community as I couldn’t trust it.’

Decades later, another layer of meaning became apparent in the Dexys sleeve of Searching for the Young Soul Rebels. The two adult males in the picture were identified. The figure in the denim jacket was a regular on the Shankill Road. The other man, leading Kevin O’Shaughnessey on to the pavement is Robert ‘Basher’ Bates, who was imprisoned for his involvement with a gang, later known as the Shankill Butchers. This team, led by Lenny Murphy, killed upwards of 19 people, chiefly Catholics. For the most part, the victims were pedestrians taken at random from the streets around North Belfast. The gang operated with butchers’ knives taken from a meat warehouse. Even by Belfast standards, their work was appalling.

Stuart Bailie

Extracted from Stuart Bailie’s book, Trouble Songs: Music and Conflict In Northern Ireland.

With acknowledgments to Gareth Mulvenna’s Tartan Gangs and Paramilitaries plus the North Belfast News.

Come on in, says Joel Harkin. Let’s talk about Memphis, the family dog who made home visits to Donegal so sweet, until she died. Let’s encounter Mark Loughrey, a mate who plays guitar in Berlin. And of course you may already know the dad and the girlfriend – twin subjects of ‘Charlie and Deirdre’, that swirling picture about separation anxiety. Come in, the gang’s all present.

Come on in, says Joel Harkin. Let’s talk about Memphis, the family dog who made home visits to Donegal so sweet, until she died. Let’s encounter Mark Loughrey, a mate who plays guitar in Berlin. And of course you may already know the dad and the girlfriend – twin subjects of ‘Charlie and Deirdre’, that swirling picture about separation anxiety. Come in, the gang’s all present.

Joel Harkin’s first album is populated by good souls and fraught circumstance. ‘No Recycling’ is a visit to Alicante where the ex-pats live carelessly while the locals are service workers. It’s a moral story about wealth inequality that’s distantly related to the punk anthem, ‘Holidays In The Sun’. And as with many Joel songs, there’s a finely tuned unease. He sings with an ache that recalls Conor Oberst from Bright Eyes while his cheap reverb pedal squalls and hums and sets off turbulence.

He writes about Belfast in the throes of redevelopment. ‘Old Churches’ is the Ormeau Road losing dignity to the wash of capital. But Joel’s most affecting travelogue is still ‘Lake Irene’. It seems to involve the Rocky Mountains and the Lisburn Road. There is cherry blossom in Kyoto and weird discourse about the way that a traveller becomes a cartoon version of himself abroad – and thus an embarrassment when he returns, cloaked in the new persona. There’s also a side story about the value of trusted friends. Quite the tune.

Onstage, Joel is garrulous and may seem gauche. But the songs tell an alternate story. He’s a fine student of human nature and he writes songs to fit peculiar, wiry emotions. His solo gigs have relied on the quiet-loud dynamic but these studio recordings have grace and diversity. On ‘Silver Line’ the pedal steel is woozy and splendid while Conor and Nicole Harper swap yearning lines like Gram and Emmylou. ‘Never Happy’, you see, is an uncommon joy.

Stuart Bailie

Joel Harkin’s album is available here

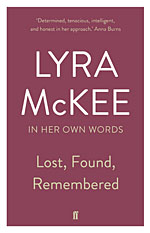

Lyra McKee wrote an article for the Mosaic website in 2016, The Fight of Your Life. It connected boxing and American football with errant behaviour and baseline poverty in Chicago and western Canada. It was about domestic violence and personality swings that were hard to figure.

Lyra McKee wrote an article for the Mosaic website in 2016, The Fight of Your Life. It connected boxing and American football with errant behaviour and baseline poverty in Chicago and western Canada. It was about domestic violence and personality swings that were hard to figure.

The stories may have seemed random but the author led you into the narrative. You trusted her and in time there was a reveal about disposable heroes, mass entertainment and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Once-excellent athletes had become concussed, paranoid, punch drunk, suicidal.

The spirit of Seamus Heaney resonates on your album, A Northern View, notably on ‘The Guttural Muse’. Did he translate easily into your music? And do you share his thoughts on the historic repression of the Irish language?

“His ideas did, certainly. The lost youth of ‘The Guttural Muse’ particularly but the language and the landscape always sounded like my language and my landscape, as I’m sure they do to many from this part of the world. Maybe the presence of his nephew’s basslines on there added a certain weight to it.

ANTHONY TONER

ANTHONY TONER

Ghost Notes, Vol. 1

RONNIE GREER & FRIENDS

Blues Constellation

There was never an Irish radiogram that didn’t stack up ‘Sample Charlie Pride’ and ‘Jim Reeves – 40 Golden Greats’. If you left the house you’d hear the same on Downtown Radio which powered up in 1976, playing ‘Okie From Muskogee’ to a listenership that bypassed the satire and banged out time on the steering wheel of the Vauxhall Viva.

What is the sound of Malojian? The sound of Malojian is ragtime and White Album whimsy, grunge, essence of parlour song and jet-powered synth lines that go hurtling across the octave. What is the meaning of Malojian? The meaning of Malojian is domestic zen, global horrorshow, empathy, endearment and gleaming soul. Is Malojian any good? Malojian is good, always.

What is the sound of Malojian? The sound of Malojian is ragtime and White Album whimsy, grunge, essence of parlour song and jet-powered synth lines that go hurtling across the octave. What is the meaning of Malojian? The meaning of Malojian is domestic zen, global horrorshow, empathy, endearment and gleaming soul. Is Malojian any good? Malojian is good, always.

Twitter

Twitter