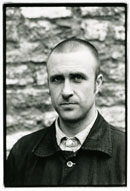

Robert Holmes had startling blue eyes and a quiet manner. He had worked as a tree surgeon and hod carrier. He painted and wrote and he often took himself up into the hills above his North Belfast home where he indulged his nature boy tendencies. He built stone cairns and found other ways to lift his experiences out of the normal.

As a boy he had witnessed the aftermath of a suicide up on Cave Hill. According to friends it had left a severe impression on him. Another time, an accident on a rope swing at Carr’s Glen left him with a broken leg. His parents Robert and Margaret bought him an electric guitar while he mended but he didn’t take easily to it. Yet as he approached his 30th birthday he started to write these peculiar songs.

Robert’s lyrics sounded like broken conversations, related over one or two chords. There was implicit danger and hurt. There was elemental stuff about the moon, the holy mountain and getting cleansed in the river. His voice had a limited baritone range and the music often sounded like a struggle between the vision and the uneven pitch of his voice, the drone forms and the fingers that labored on the frets.

He was an outsider artist, not unlike Skip Spence, the busted traveller from Moby Grape who wrote his ‘Oar’ album in a psychiatric hospital. There was a twist in Robert’s consciousness that disallowed him from writing workaday, attractive songs. The music was sometimes naïve and spooked like Daniel Johnston. This wasn’t a career plan or a wealth creation scheme. It was a straight-up artistic effort. He said that his material was “stuff that goes on in your head and trying to hammer things out. Fighting with things and trying to make peace with things.”

Robert remortgaged the small family home, bought a decent acoustic guitar and in 2008 he released a CD. The lead track was ‘Hazard Hill’ a nocturnal ramble, fetching the Ballysillan blues out of the Murder Triangle. It prompted a few radio plays and sessions as well as comparisons to Nick Cave, Mark Lanegan and Jim Morrison. This writer, perhaps thinking of the actor Joe McGann or the band Shack, talked of his “Scallydelic” potential.

His friend Marty Neill helped to introduce Robert to the city’s music scene.

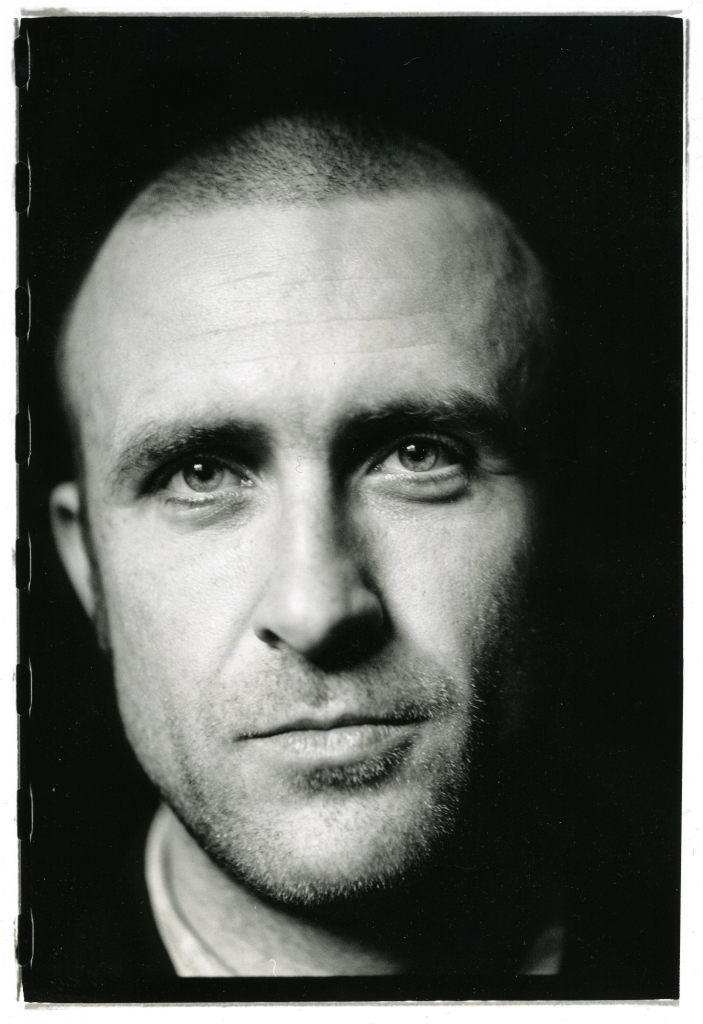

“My first experience of Robert was when we were 14. Robert was a philosopher and called himself a lay preacher. I’d never met anyone like him. He was talking about the ‘silent revolution’, about how things were changing. He always had that vision. But that dark aspect was always there.

“We worked together at the Stadium Community Centre in the Shankill, which was half-full of Christians and half-full of lifers who’d just been let out of jail. An extraordinary place. He started writing songs in his late 20s. No one expected this to happen. He had this voice that was unbelievable – where did this come from?”

According to Marty, “he could write the songs but he couldn’t do all the other stuff”. So while there were some like-minded people in the scene, he was often awkward and ill at ease. He took a booking at Lavery’s Bar, turning up for a 7pm soundcheck, as requested. By the time he took to the stage at midnight, he was drunk and unable to recall the lyrics. His mate, who was playing maracas, kept knocking the microphones over as the performance turned rowdy. “I got a lot of aggression out,” he told NVTV later, “and a lot of anger. It was cool that way, but a bit embarrassing. “

The songwriter Robyn G Shiels encountered him around this time.

“I first met Robert round the time Josh T Pearson played a solo gig in Lavery’s, years ago. Desert Hearts were supporting so myself, Charlie Mooney and Bob immediately hit it off via the usual sleggin’ each other off and many a drink was drunk and had. We played in McHugh’s Basement later that same year to all of the lucky or unlucky 13 people who made it to the Brothers Doom on the night! Both of us wondering why there wasn’t more folk down to witness such a pairing of amazingly talented minds that night. Ah well, their loss, we thought.

“Robert was one of a kind, a strikingly handsome man with a bellow in his voice that wouldn’t have been out of place in any Mark Lanegan album but also walked it like he talked it. It was only a matter of time – I thought – that he would get a major record deal and leave us all standing.”

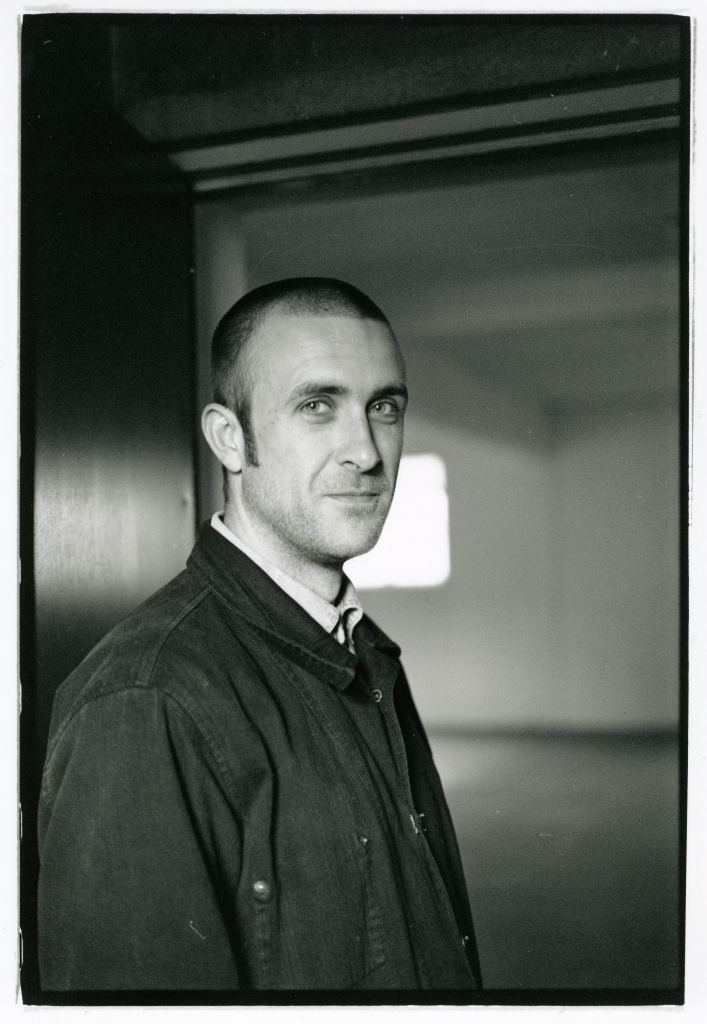

In 2008, Robert took over the management of the Backbeat record shop in Haymarket Arcade. It was a semi-hopeless case. He released an EP, ‘Infant Rising’ in 2010. It alternated between ‘Into The Light’ and the morbidity of ‘Something In The Blood’. Aside from this he made a memorable video on Cave Hill. He sang ‘John Boy’, writing in code about paramilitary drug dealers from the area. Media interest may have diminished but another songwriter, Tony Wright was partnering up.

“Rab and I used to meet up on Saturdays to jam and work on some tunes he was developing for his debut album. We started off with in the AirPOS offices beside the Duke of York then in his little studio on the third floor on Donegall Street.

“Some weeks we just talked and laughed, guitars never leaving their cases – but every week I left staggered by his creativity. He viewed the world in a deeply spiritual way and I always walked away smiling and with a little more hope in my heart. Rab was the single most effortless songwriter I’ve ever encountered and could make or break your heart with a simple turn of melody and phrasing, all whilst making you tap your feet and nod your head along with the song’s heartbeat.”

There was talk of him working with a name producer but that plan didn’t develop. Instead, Robert would send out occasional recordings and semi-formless jam sessions, the covers adorned with drawings of horses’ heads and orbiting eyeballs. There were rumours of mental health issues. There were domestic problems and even close friends found it hard to engage, as Marty admits.

There was talk of him working with a name producer but that plan didn’t develop. Instead, Robert would send out occasional recordings and semi-formless jam sessions, the covers adorned with drawings of horses’ heads and orbiting eyeballs. There were rumours of mental health issues. There were domestic problems and even close friends found it hard to engage, as Marty admits.

“You say, ‘well, you can be very difficult, very challenging as a person – intense, scary at times – also you’re the most hilarious human being I’ve ever met’.” Later, this became more accented. “The toxicity – it was palpable. It was like a presence in the room. He was the best ever at not talking. Just an intense stare and then, four words. The depths were very deep indeed.

“The songs are an honest documentation of all of those things. The songs he was writing in the last year of his life are jaw-dropping. For their content as much as anything else. The shame is that I’ve heard 120 songs and most people have heard five and they’re probably the darkest five. I’ve heard stuff that was extraordinarily hopeful as well.”

In 2018, Robert seemed healthy. He was off the drink, attending church and had joined a walking group. Marty met him in town on the way to a therapy session. The singer was carrying a painting for his therapist and she was apparently going to write him a song in return. Also there was a phone recording of Robert at the piano, singing his own gospel song. It was called ‘Push Back the Darkness One More Day’. At the end of the short clip, he looks away from the intensity with a bashful smile.

His last sighting alive was October 17. His body was found at the Three Mile Water area, Newtownabbey, a week later. There was memorial service at Greenisland Baptist Church. People brought along his paintings and hand-made poetry books, evidence of his art. This was all the more impressive because Robert had burnt a lot of his work. The video of ‘Push Back the Darkness’ was widely circulated online.

“I miss him dearly,” says Tony. “And I’m so sorry I’ll never hear his soul in person again, but always grateful that I got to witness his greatness, spend time with him and see how he crafted his finest of art. There’s a corner in Belfast where Holmes Street meets Hope Street – I’ll always smile a longing smile when I pass by it and think of my friend, Rab.”

According to Marty, there may be a posthumous release of Robert material.

“There are people who wanna take it forward. And I really hope they can. I think it would be a shame if those songs don’t make it out into the world and don’t serve their purpose. Because the purpose for him was that he would give those to people. He didn’t know where they came from and they weren’t his – as far as he was concerned. The whole purpose was to give them to other people.

“You can talk about the darkness in Robert’s songs. He could write dark songs and do them in a serious way, he wasn’t pretending. But he would also write songs that were full of great hope. And he looked at this place very differently. The loss is really huge.”

Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter