The Alternative Ulster fanzine had asked Jake for a song that they might use as a flexidisc. He obliged in February 1978, using the fanzine title to imagine an empowered, shared space, the punks united against the bigots. Jake says he was chiefly the author of the song, although Gordon Ogilvie had provided the wordplay of “alter your native land”. The song was declined by the fanzine but Stiff Little Fingers had another flaming tune in the songbook. Also, they were working on their version of Bob Marley’s ‘Johnny Was’. Some liberties were taken with the words, Henry says.

The Alternative Ulster fanzine had asked Jake for a song that they might use as a flexidisc. He obliged in February 1978, using the fanzine title to imagine an empowered, shared space, the punks united against the bigots. Jake says he was chiefly the author of the song, although Gordon Ogilvie had provided the wordplay of “alter your native land”. The song was declined by the fanzine but Stiff Little Fingers had another flaming tune in the songbook. Also, they were working on their version of Bob Marley’s ‘Johnny Was’. Some liberties were taken with the words, Henry says.

“I think we were up in Gordon’s flat and he was playing the album ‘Rastaman Vibration’. We knew The Clash had done (Lee Perry’s) ‘Police And Thieves’ and we liked their version of that. And it was like, you know, it would be good to put a cover on the album. The original version we did on a demo changed the names, it was like, ‘Paddy was a good man’, ‘Frankie was a good man’, ‘Billy was a good man’ – we changed the names all the time. And then we just left it to the original.”

Stiff Little Finger’s ‘Alternative Ulster’ had started as a squalling tantrum about the lack of social amenities in Belfast, but the lyric carried extra weight and the band and its audience invested in its meaning. It became their most important song. Brian Faloon considers this.

“It did become an anthem. Yes, we might have pushed it a little bit in terms of our anger. There were people who were far more repressed that we were – for example in our area we weren’t getting nightly visits from the British Army, kicking in doors and stuff. That was happening on the Falls Road, or in the New Lodge or Whiterock or wherever. But we realised that was happening, that there’s a level of repression going on which outweighs any conscionable action.”

“It did become an anthem. Yes, we might have pushed it a little bit in terms of our anger. There were people who were far more repressed that we were – for example in our area we weren’t getting nightly visits from the British Army, kicking in doors and stuff. That was happening on the Falls Road, or in the New Lodge or Whiterock or wherever. But we realised that was happening, that there’s a level of repression going on which outweighs any conscionable action.”

And in Belfast, he notes, Stiff Little Fingers were attacked by the community papers on both sides.

“I remember reading both the Woodvale News and An Phoblacht on the other side. And both of them criticised us quite heavily for the stand that we took. We thought, we must be doing something right if they’re both pissed off at us. Because the stand was, you’ve got nothing to offer anybody, other than sectarianism or death or imprisonment or a life of fear, which you also subject the rest of us to. So lyrically and musically, we had no truck with them, so equally, we were criticised. That was great.”

A 28 date ‘Out Of The Darkness’ UK tour with the Tom Robinson Band put Stiff Little Fingers before an audience that was young and receptive. Tom was singing about sexual politics (notably, ‘Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay’) and fronting the Westminster establishment. So if his Belfast support act was also tilting at prejudice and systemic failure, there were many ears prepared to listen. Even so, Brian Faloon was surprised. “We’d get 17 year olds coming back, full of enthusiasm for what we were doing – both musically and in the context of what we were trying to say. That took us aback.”

Tom Robinson had promoted his ‘Power In The Darkness’ album with a 12 inch stencil, packed into the album sleeve. It had been designed at the Socialist Workers’ Party print shop in London and it depicted the Gay Liberation fist, a variation on the Black Power salute. There was a proviso that “this stencil is not meant for spraying on public property”. It was an integral part of the singer’s branding, and there were no qualms about taking this to their gig at the Whitla Hall in Belfast. In the city, Ian Paisley and his followers in the Free Presbyterian Church were still railing against the partial liberalisation of homosexuality in the UK and had presented their own campaign, Save Ulster From Sodomy, in 1977. They had attracted 70,000 signatories. Tom Robinson was pleased to note that not everyone had signed up and also that the stencil was doing its work.

“When we went to Belfast, Catholic kids took us on a guided tour of The Falls. And there was the fist, on the ends of buildings.”

Stiff Little Fingers were invited to play at the second large-scale Rock Against Racism event at Brockwell Park, Brixton on September 24 with Elvis Costello and Aswad. They took a place on the bill after Sham 69 had received death threats from right-wing elements of their fanbase (Jimmy Pursey did make however a speech at the gig). This was a significant event for the band since a right wing minority continued to view them as anti-IRA and therefore on their particular side. There was also a deal of confusion over the anti-racist lyrics of ‘White Noise’ when the bigoted name-calling was sometimes taken at face value. “People would Sieg Heil at a few shows,” Jake remembered, “and a couple of times it descended into punch-ups. Any band that was perceived as punk was fair game.”

There were issues with Loyalists at the Merville Inn in Belfast and an IRA threat when they played in Drogheda. “The local boys had warned the promoter that he should not be putting this band on,” says Ali. “The promoter was actually persuaded by the fact that the show was packed out by quite a few punters. To see what all the buzz was about.” Still, satire was a problemic weapon, and this issue followed the band on a later song, ‘Fly The Flag’. It was a send-up of patriotism, but Henry remembers a few instances when the irony was missed.

“We used to get people throwing things at us when we played it in Dublin. I don’t think they got the point of it. ‘Fly The Flag’ used to get to people, for years, when we played in the Republic. Obviously that’s a generalisation because there were a lot of people did understand it of course. But yeah, it got us into a few scrapes.”

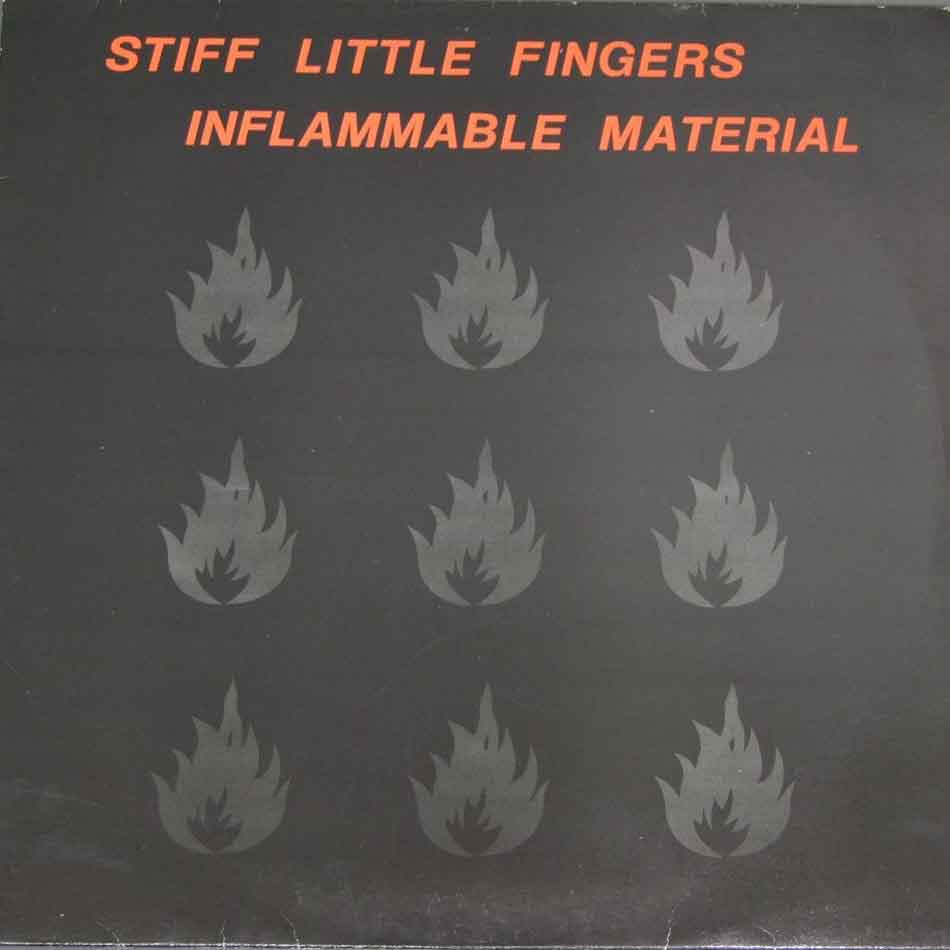

The debut album ‘Inflammable Material’ was released on February 2, 1979. While there were some vocal critics at home, the band was warmly recognised by writers such as NME’s Paul Morley. Again, it was the independent label Rough Trade that managed the release and the astonishing logistics of getting a DIY record into the UK charts. “It was definitely the first completely independent to ever break the official UK Top 20,” Jake says. “It went in one place higher than Barry Manilow’s Greatest Hits which I was always really proud of. It actually did go into the charts on my 21st birthday so that was the best present you could have ever hoped for.”

The debut album ‘Inflammable Material’ was released on February 2, 1979. While there were some vocal critics at home, the band was warmly recognised by writers such as NME’s Paul Morley. Again, it was the independent label Rough Trade that managed the release and the astonishing logistics of getting a DIY record into the UK charts. “It was definitely the first completely independent to ever break the official UK Top 20,” Jake says. “It went in one place higher than Barry Manilow’s Greatest Hits which I was always really proud of. It actually did go into the charts on my 21st birthday so that was the best present you could have ever hoped for.”

Also there was ‘Barbed Wire Love’, a star-crossed conflict ballad with a doo-wop breakdown. Somewhere between Shakespearian tragedy and the maudlin schlock of vintage weepers like ‘Leader Of The Pack’. Stiff Little Fingers, with the assistance of a bottle of vodka had written themselves out of a depressive state (freshly rejected by Island Records, Brian had announced his departure) by loading up on terrible puns and mocking their own seriousness. Henry was teetotal, but he was happy to participate.

“There’s 13 tracks on that album and I think five of them were about Northern Ireland, which people sort of tend to overlook. But they were all very serious. So we thought, is there a way we could do a light-hearted song about The Troubles but not be offensive? It was basically a case of sitting down and coming up with the most ridiculous lines – “you set my Armalite”. The whole point was to say, ok, it’s bad, it’s dark times, but people still live and have fun and I think that was the whole point. We got people who would say, is it about drugs? You set my arm alight? People don’t know what an Armalite (assault rifle) is, which is fair enough, why should you?

“There’s 13 tracks on that album and I think five of them were about Northern Ireland, which people sort of tend to overlook. But they were all very serious. So we thought, is there a way we could do a light-hearted song about The Troubles but not be offensive? It was basically a case of sitting down and coming up with the most ridiculous lines – “you set my Armalite”. The whole point was to say, ok, it’s bad, it’s dark times, but people still live and have fun and I think that was the whole point. We got people who would say, is it about drugs? You set my arm alight? People don’t know what an Armalite (assault rifle) is, which is fair enough, why should you?

“A few weeks ago we (XSLF) were doing a gig down in Drogheda and the guy came up to me and he said, when you guys came out, I was one of the guys walking around with black flags and during the days of The Troubles I would have signed up for the IRA. He said, and I heard ‘Inflammable Material’ and it really made me think’ He actually said to me, I want to thank you for that. It can sound corny but it’s nice to hear. I’m not one of the ones who says that ‘Inflammable Material’ changed everybody’s life’ – but it changed some people’s.”

Stuart Bailie

(An extract from Trouble Songs by Stuart Bailie. You can buy the book here).

Twitter

Twitter