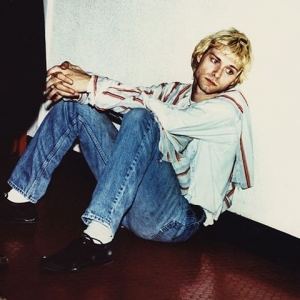

Aftershow at the King’s Hall, Belfast, June 22 1992. Nirvana have finished their last ever indoor gig in the UK, ending with a ferocious ‘Territorial Pissings’. Around 12,000 fans have been drunk, teenage, unbelievably joyous, puking in corridors and dry-humping in alcoves. Now Kurt sits alone on the floor of the hospitality area, his back to the wall, his hair hacked short, keeping himself low and unremarkable.

Dave Grohl is drinking Guinness. Krist Novoselic is affable enough. Members of Teenage Fan Club and The Breeders wander in. Courtney Love is six months pregnant, smoking, loudly at war with the security firm. At one point she had rushed onstage during the Breeders set, remonstrating. There was a drama about a puppy being smuggled into the gig and the exchange of a mohair jumper. She procures it for Kurt. “Get them some cocaine!” she yells.

Victoria Clarke, the writer and partner of Shane MacGowan is there. There is talk of her starting on a Nirvana book, but that will end badly. Steve Pyke, another Pogues associate, is taking photos for Select magazine and had spent part of the afternoon doing a session with the band around the agricultural buildings at the back of the venue. Another guest is David Cavanagh, a fine journalist who has been talking to the band for a Select feature.

David speaks quietly but mostly in an intense manner. You can hear bits of Dublin in his voice but also some Belfast inflections, due to his schooling at Methodist College. He had played in a band (The Superheroes) during the post-punk era, sharing a bill around 1982 with my own group at the Pound on Townhall Street, a famously rough place. Some of David’s music obsessions were later fictionalised in his book Music for Boys. He wrote about the music weeklies and their disproportionate value for provincial youth. Likewise with the John Peel radio show, followed just after in an Irish evening by Dave Fanning, broadcasting from Dublin. He added catty tirades about local NME and Melody Maker stringers: Adrian Maddox and Robert Scott were subject to parody in the book, along with their band, Palace of Variety. There is further anguish in that the central figure in the story is hopelessly introverted and the love is not requited.

David speaks quietly but mostly in an intense manner. You can hear bits of Dublin in his voice but also some Belfast inflections, due to his schooling at Methodist College. He had played in a band (The Superheroes) during the post-punk era, sharing a bill around 1982 with my own group at the Pound on Townhall Street, a famously rough place. Some of David’s music obsessions were later fictionalised in his book Music for Boys. He wrote about the music weeklies and their disproportionate value for provincial youth. Likewise with the John Peel radio show, followed just after in an Irish evening by Dave Fanning, broadcasting from Dublin. He added catty tirades about local NME and Melody Maker stringers: Adrian Maddox and Robert Scott were subject to parody in the book, along with their band, Palace of Variety. There is further anguish in that the central figure in the story is hopelessly introverted and the love is not requited.

The real-life David doesn’t do small talk so well, but there’s a story about his University studies in Russian, mention of financial scrapes and his early scrounge existence in north London. When he talks about music, it is with utter surety. He knows the dates, the line-up changes, the stats and the cultural resonance. He seems particularly sensitive to the emotions that are latent in popular music. There’s a sense of mission – he takes his work seriously when many of his peers will prefer the fun and the freeloading. In rock and roll terms, he’s like a Jesuit or a Rabbi. Consequently, Select is starting to out-perform the more established music press and Cavanagh, a former Sounds writer, is well regarded.

So it is at the King’s Hall when he makes a series of abrupt departures from the chit chat. An idea comes to him and so he steps over to Kurt, bends down with his tape machine and issues a series of questions. The singer puts out some thoughts, the machine clicks off and David rejoins the other guests. This happens three or four times but nobody queries it and Kurt tolerates the incursions into his quiet space. It’s how David operates.

The Select feature is tremendous. He writes about the tumult in Belfast, the dynamic of an alt-rock power couple, the drug rumours (Kurt was taken to the Royal Victoria Hospital hours later, officially suffering from a weeping ulcer), the gate-crashing puppy and he witnesses a moment that involves Kurt, Courtney plus a peanut butter and jelly sandwich:

The Select feature is tremendous. He writes about the tumult in Belfast, the dynamic of an alt-rock power couple, the drug rumours (Kurt was taken to the Royal Victoria Hospital hours later, officially suffering from a weeping ulcer), the gate-crashing puppy and he witnesses a moment that involves Kurt, Courtney plus a peanut butter and jelly sandwich:

She shoots him a look of quite disgraceful coquettishness and breaks a piece of the sandwich off. Then she lifts it, very carefully to his mouth. Their eyes meet. When he opens his mouth she opens hers too, just like a baby and his mother. They ogle each other. Wow. He pouts and in a kooky, helium-pitched baby Donald Duck voice quacks: “Feed me”. She grins” “Good boy…” She turns to me.

“I’m Courtney, hi. I married someone more famous than me.”

David wrote perceptive and nuanced stories for Uncut, Q and Mojo, most recently a profile of Ian McCulloch. There was a monumental narrative of the indie scene and Creation Records – My Magpie Eyes Are Hungry for the Prize. There was a study into the socio-cultural import of John Peel, Good Night and Good Riddance. Have a listen here to an interview with Dave Fanning to understand Cavanagh’s precision and scholarship.

David wrote perceptive and nuanced stories for Uncut, Q and Mojo, most recently a profile of Ian McCulloch. There was a monumental narrative of the indie scene and Creation Records – My Magpie Eyes Are Hungry for the Prize. There was a study into the socio-cultural import of John Peel, Good Night and Good Riddance. Have a listen here to an interview with Dave Fanning to understand Cavanagh’s precision and scholarship.

Additionally, there is a chapter in a compendium of music fandom called Love is the Drug, published in1994. He writes about witnessing The Triffids in 1983-84. He becomes infatuated, awkward, transported. There is a parallel story of his failing at the Slavonic and Eastern European Studies at UCL, Bloomsbury, about paranoia, penury and a romantic attachment that goes alarmingly wrong. There is some comfort in his new Australian friends and in his vinyl companions: Miles, Syd, the Byrds and Beefheart.

News of David’s death reached us yesterday. He was 54. There are no details as yet, other than a steady roll of tributes, from players and writers, including John Harris in the Guardian. He was not a social media person, so biographical information is limited. He was about the word, the tome and the conviction. In that sphere, David was untouchable.

Stuart Bailie

(David Cavanagh, 1964-2018)

Twitter

Twitter