In the early hours of May 7, 1992, Richey Edwards slipped a postcard under the door of my hotel room at the Sofitel, Beverly Hills. I looked at it and smiled. We had been shopping together on Melrose two days before when he had bought the Barbie card. It pictured the famous doll in her boudoir, with a speech bubble that read, “Every morning I wake up and thank God for my unique ability to accessorize.”

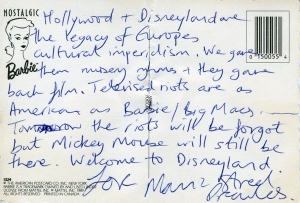

On the other side, he had written a message in his singular, scattershot style. “Hollywood and Disneyland are the legacy of Europe’s cultural imperialism. We gave them nursery rhymes and they gave us back film. Televised riots are as American as Barbie / Big Macs. Tomorrow the riots will be forgot but Mickey Mouse will still be there. Welcome to Disneyland. Love Manic Street Preachers.”

I miss Richey. He was remarkable. He was the chief propagandist for the Manics in the early days, sending feverish letters to music writers from his home in Blackwood, south Wales. Along with Nicky Wire, he wrote those early lyrics about the banking system and the porn business, about suicide alley, the monarchy and the radiant despair of youth culture. He had carved the legend 4 REAL into his forearm with a razor blade when Steve Lamacq had questioned his authenticity. Not the most stable human being, but he was smart and soulful and he laughed more than people would give him credit for.

Now here we were in Los Angeles, at the launch of their debut album, ‘Generation Terrorists’. There had been a fearless gig at the Whiskey on Sunset Strip, and an afterparty at the Rainbow afterwards. We were hanging with Rodney Bigenheimer from KROQ and hearing stories about LA lore. I was amused by the Manics splash mats in the urinal and I met their American manager who also represented Billy Joel.

The band wasn’t especially thrilled. Melancholia was their default position. Also, some of that bravado was wearing off. They had promised to sell 16 million copies of their first album and then self-combust, setting fire to themselves on Top Of The Pops. But sales had been modest and the music industry was co-opting them into more conventional deal. Meantime, they had arrived in America in the middle of the LA riots and the city was literally smoking. What chance for these Welsh punk revivalists?

On May 6, we had travelled to Venice Beach for a photo session. The army was on manoeuvres on the sand and the band had been anxious to avoid a contrived image, like those famous Clash shots in Belfast. So we headed off to a TV show in Anaheim, where Richey looked bothered. While he waited for his vapid interview, he opened up a paper clip and started to gouge a hole in his hand. His manager, Martin Hall asked him to desist and soon after the job was done and we were headed for Disneyland.

Which was fun, actually. I sat with Richey on some ridiculous space ride and he was screaming like a child. The NME photographer was Pennie Smith, who had taken all those Clash shots and she was getting busy with her Pentax. Our pleasant valley interlude was over soon enough and the band dropped me off for an interview in Compton with Eazy-E from NWA. Foolishly perhaps, I got my riot story in this intense place before regrouping with the Manics at Barney’s Beanery on Santa Monica Boulevard, a rock and roll location.

Janis Joplin had drunk there the night before she died. Charles Bukowski had been a regular barfly and Jim Morrison was ejected for relieving himself in front of the patrons. Our session was more moderate, although Richey got loaded on tequila and talked for an age – about Van Gough, the impossibility of a perfect circle and the innocence of a child’s eye. We all tried to draw perfect circles on napkins. It was silly. Richey muttered about the trade-in between Europe and America, from Fritz Lang to Walt Disney. He was getting morbid again. But the night got even more twisted when he took an allergic reaction to the alcohol and his arms turned red and started to swell.

The soft scar tissue puffed out even more and thus we witnessed a three dimensional rendition of 4 REAL on Richey’s arm, like something from a Cronenberg film. Meantime, the many cigarette burns, the lesions and cuts had turned scarlet on his skin. “The war wounds,” he acknowledged.

Richey delivered the postcard to my room a few hours later. Thereafter, the Manics left for Japan, for some live shows and a video shoot in Tokyo for ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’. I met Richey a bunch of times afterwards, but the encounters were increasingly cheerless. Notably there was an interview at Blue Stone rehearsals in Pembrokeshire in 1994, just after he had left The Priory. He was listening to ‘In Utero’ and insisting that “the S word” was not an option. He vanished altogether in February 1995. Not a word since. I really wish he would write.

Twitter

Twitter