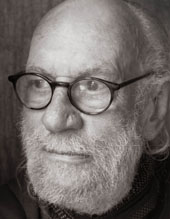

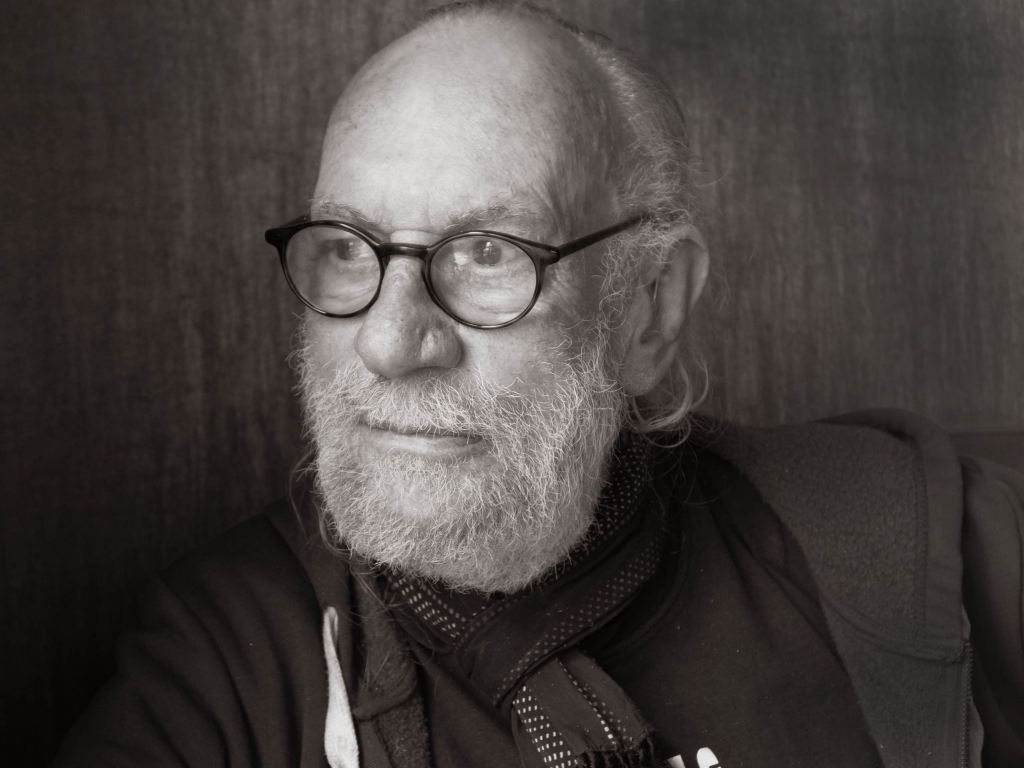

The health is not great and Jackie Flavelle is sore because he can’t load up the gear and go touring with his bass and his comrades in jazz. It’s the life he has known for 60 years. His talk is hepcat jive and north Belfast grit. He cusses often and the eyes are undimmed behind those lenses. Medical procedures will keep him off the road for some time, tethered in Donaghadee. He will be 79 in October. Time to pause a moment and review a substantial life.

The health is not great and Jackie Flavelle is sore because he can’t load up the gear and go touring with his bass and his comrades in jazz. It’s the life he has known for 60 years. His talk is hepcat jive and north Belfast grit. He cusses often and the eyes are undimmed behind those lenses. Medical procedures will keep him off the road for some time, tethered in Donaghadee. He will be 79 in October. Time to pause a moment and review a substantial life.

“I’ll tell you anything you want to know…”

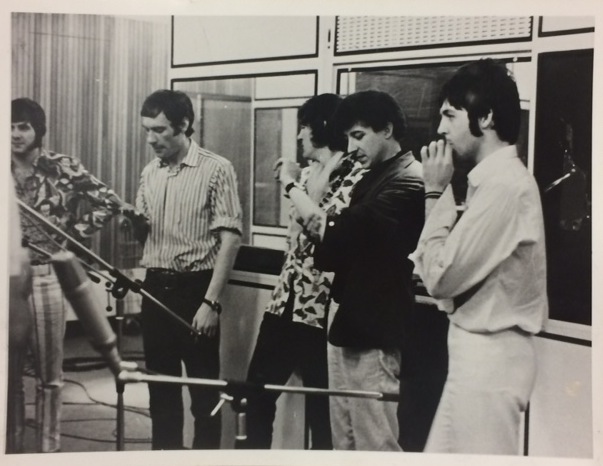

We’ll start then with July 20, 1967. Jackie at work in Chappell Studios on Maddox Street, London. He’s been with the Chris Barber Band for a few months and he’s working on a track called ‘Cat Call’. The author of the tune is Paul McCartney. He had written it ten years earlier, during his days in The Quarrymen. The Beatles had played around with it in 1962 but not granted the instrumental a proper recording. But now, Paul and Brian Augur are adding keyboard parts and the Barber Band has summoned up the rude character of New Orleans jazz.

“Paul wrote that tune for the Barber Band, donkey’s years ago,” Flavelle explains. “He always wanted the band to play it. And eventually he just hired the band.”

They had already rehearsed ‘Cat Call’ upstairs in the Tallyho pub in Finchley. There was a tuned piano and the stink of stale beer and after learning the song parts they went downstairs for pies and pints. They visited the Marquee Studio for a session next, but Paul didn’t like it, so they decamped to Chappell Music, just off Bond Street. Paul was there with his girlfriend Jane Asher. She was running out and getting beer after the refreshments had gone. There was a whip round and everyone put in a pound, except McCartney, who didn’t carry cash. Graham Burbidge, drummer with the Barber Band loaned him a quid.

Macca had white trousers, white calfskin sneakers and “about a hundred quids’ worth of silk shirt”. The session was nominally produced by Georgio Gomelsky for his Marmalade label. He was already a bit of a legend – boss the of Crawdaddy Club where The Rolling Stones had established their domain. He also managed The Pretty Things and sure enough, Viv Prince from the band was at this session also. They all roared and catcalled on cue and Georgio thundered “Please play slower!” to great effect. It was a month after ‘All You Need Is Love’ and the dust was barely settled on ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’. Now here was McCartney at the mixing desk, attending to Jackie’s bass tone in this modest production, giving it some of the presence of those famous Beatles records.

“I’ll tell you a funnier thing. After we’d finished the last session, it was about midnight. And we were parked outside Chappell Music. I had the old Cortina estate parked outside the studio. Paul and I and Jane left together. We were standing yarning and I was parked behind his Aston Martin DB5. He says, where do you live? I said, I’m not too far away from you, I’m in West Hampstead. He says, come back to the house for a drink. I says, Paul, I’d love to but I have to get up at six in the morning, and we’ve a gig in Paris tomorrow, launching the label. And he went, lucky bastard, I’d love to be going to Paris. ’Cause, you see, they weren’t doing any gigs.”

Flavelle had started gigging as a teenager with Dave Glover, who regularly pulled two thousand people into the Arcadia Ballroom in Portrush and swung the culture into the showband era. This was a significant jump for Jackie, who had been orphaned at five, losing his mother just after his birth and his serviceman father during the war. Growing up on Duncairn Gardens, he had been mentored by William Flavelle, his dad’s older brother.

“Billy worked as a labourer but he was a really really good musician. A fine flute player. And he conducted the church choir – North Belfast Male Voice Choir, and the Ulster Amateur Flute Band. He started me on the flute when I was about seven.

“I worked my way through the flute band. Then when I went to college (RBAI) I played flute in the orchestra. The orchestra was brilliant, it got you out of everything. And then to make totally sure, I joined the CCF (combined cadet force) and that got me out of rugby, so I wasn’t killed any more. I was quick, I could run like fuck, man. I sort of enjoyed it but I was the wrong build.

“And then I started playing the double bass with Dave Glover’s dance orchestra. I was 19. It was a very good job to have when you were 19 because it was professional wages. Glover – he was a fucker, but he knew the business. He knew how to run a band. He taught me a lot actually. I fell out with him loads of times, once seriously. When I look back on it, he was right. It was no easy job.”

Chris Barber was a major name in British trad jazz and was party to a messy by-product that was skiffle. Seminal players like Chris and Ken Colyer had prepped the conditions for this youthquake but Lonnie Donegan had given this folk-blues mutant a voice and a verve.

“My inroads into all this started with Lonnie Donegan,” Jackie concurs. “I heard Lonnie and the whole world just opened up. The boys were all going down the rock and roll road. I didn’t, because I discovered Lonnie and got into the blues – Big Bill Broonzy and Lead Belly and all. And that took me in an entirely different road. I never played in a rock and roll band, but I could easily have done.”

After a significant bust-up with Dave Glover, Jackie spent time in Derry with Johnny Quigley and was then active with Galway’s Swingtime Aces. But he was back working with Glover in late 1966 when Chris Barber and his partner Ottilie Patterson paid a visit to the Queen’s Hall in Newtownards.

“Ottilie was the best blues singer in Europe, never mind here. She was so fucking good, man. Her mother was living in Newtownards. She had come over to see her – she was sick. And we were doing a gig in the Queen’s Hall. Chris and Ottilie walked in. I recognised him, like. We had a bit of a yarn in the break, and that was it. About six months later – this is hilarious – we were in another Queen’s Hall, this time in Ballycastle. We were doing an Irish tour. Of all the places, the chances of trad jazz being popular at the Queen’s Hall in Ballycastle was less than negligible. I didn’t know anything about this at all, but at the end of the gig I was talking to the band. It was my turn to drive the band coach, so I was locking the back doors and Chris came down the steps with Ottilie in a fur coat.

“And Ottilie says, well, just ask him. And he came over and says, would to join me for breakfast – we’re staying at the Landsdowne Court Hotel. I said, Ok if I bring the missus? He says certainly. So we’re sitting having breakfast and the band’s all staring at me, like. And out of the blue he says I need a bass player – someone who plays bass guitar as well as double bass. And he says, I need somebody who likes the blues and I’ve heard you play and you fit. Do you want to gig? I just couldn’t believe it. So it got me out of showbands. I got to London while it was all still happening in 1966. And it was absolutely just fucking brilliant.”

So was it musically demanding?

“They were playing more or less just New Orleans jazz and blues. But after I joined and we got the bass guitar in, we started to get more progressive. In the ’60s and ’70s it was a very, very good band. We played contemporary blues. We started doing stuff by The Band.

“I’ll never forget the first gig. Up in a jazz club in Leicestershire. Chris drivers everywhere like the hammers of fuck. And I went up in his Alpha Romeo two litre Ti. It was great gig and I played a few tunes. I was a bit nervous but everyone was more or less dead nice. We got back into the car. Chris took off about a million miles an hour in the rain. And about two miles down the road, he lost it. We went over a hedge backwards into a field. It was a miracle that nobody was hurt. We missed every tree and just spun around in this bloody field. So I nearly died on my first gig. I was sitting in the middle of this field thinking, fuck me, Eddie McIlwaine (showbiz writer for the Belfast Telegraph) will love this… ‘Flavelle dies in his first gig with Barber’.”

Ottilie Patterson was a stunning singer, inspired by the deep blues of Bessie Smith. She was the defining voice of post-war jazz in Britain. And she had grown up in Comber, County Down.

“It’s a beautiful story. Her father was in the Royal Army Service Corps in the First World War. He was stationed in Latvia and he met Ottilie’s mother. And after the war he brought her home to Comber. She was a tall and extremely attractive lady. But she didn’t speak a word of English, never mind Comber. He had a good job, he was chauffeur to the Andrews Family that built the Titanic. Ottilie moved in all the right circles from an early age. She went to art college and she was the art mistress in Ballymena Academy. And she went to holidays in London and ended up on stage with Chris and that was it. Great woman.

“Ottilie was a natural born blues singer. Even the Americans loved her, man. She was just ahead of the pack. Everyone who sings the blues that came after copied her. Elkie Brooks and all those people – they were Ottilie fans. She understood it, she had the voice.

“One of her problems was that she had a really high IQ, which meant that she was smarter than Chris. And there’s nobody smarter than Chris, if you know what I’m saying. I mean that literally as well, he’s so clever, man. And so they ran into problems within their personal life. Then it got to the stage when Chris couldn’t get a gig without Ottilie. They wouldn’t book the band. So he started to roar out, basically. He didn’t want to have to have a girl singer, to get work for the band. Eventually it worked. He reconstructed the band. And we never had a pro singer again.”

And at the same time, trad jazz was in decline?

“It was over. All the jazz clubs turned into rhythm and blues clubs virtually overnight. The Cavern and all – they were jazz clubs, man. I played them all. The thing is, though the British work dropped off a bit, the work in Europe held out. Chris was always huge in Europe. And he still is to this day. He gets more awards than enough. He walks on the stage on these concert halls today and then he gets a standing ovation before he even says a word.”

The Barber Band played three nights in at the Friedrichstad-Palast, East Berlin, November 25-17, 1968, later released as a live album, fervent and blazing.

“That was some trip. They wouldn’t let us over the border at first. It was like being in The Beatles. We got to this place in the centre of town. It was a huge concert theatre and there are banks of cameras from all over the Eastern Bloc. Because they didn’t get any western bands.

“It was like being a rock star. It was more or less the same thing. And we knew them all anyway because of the connection between the Marquee and the 100 Club. We knew everybody in the rhythm and blues rock scene, like. All sorts of people used to get up. Rod Stewart used to do it all the time and Long John Baldrey. Rod was in Steampacket and Ottilie said, that fucking band ruined his voice. He used to sing like an angel. But his broken voice made him a fortune.”

Do you remember much about recording ‘Dixie Toot’ with Rod Stewart?

“I remember all about it. Unfortunately, we weren’t in the photograph (the gatefold photo on Rod’s 1974 ‘Smiler’ album). I was fucking raging, because we were away when that was taken. We were on the road somewhere. ‘Dixie Toot’ was supposed to have a video which launched Rod in America, from what I remember. We went to a pub somewhere in south London near Battersea near the river. Which was the Barber Band and Rod, but that was it. It was never released. And everybody has looked for it since, including Rod. “

Flavelle met Bowie at the Marquee also – the latter spent the ’60s in a perpetual hustle and he wanted to sweet talk the venue’s manager Jack Barry into a gig. Some of the connections were stranger, like the invitation around 1972/73 to rehearse with The Doors.

“That’s another bizarre story. Steve Hammond who eventually joined the Barber Band on banjo – they were all mates. The Doors were living down the road from me, at St John’s Wood. Steve rang me and said, The Doors wanna bring in a bass player and I’ve given them a list of three or four, expect a call. I mean I’ve not listened to The Doors. So I listened to The Doors. I thought, that’s a bit rough but I suppose they’re all right. I went down to south London, they had all the gear set up. I played with the guys, but I didn’t suit them and they didn’t suit me. It came down to two bass players. Me and a guy from New York who was playing bass with Carly Simon (Leland Sklar). He got the gig and I wasn’t sad about it. The only one who was sad about it was Noreen my wife, ’cause she thought she was gonna be living in a ranch in California.”

Jackie saves his warmest smiles for the memories of Sonny Terry – a 25 stone harmonica-blowing legend from Greensboro, Georgia. They drove together over the autobahns in Jackie’s Cortina while the bluesman told stories of the American railroad and adventures with Woody Guthrie. And of course there were encounters with the jazz greats. Jackie’s last gig with the Barber Band in 1977 was at the North Sea Jazz Festival at The Hague. Duke Ellington and Count Basie made a swell entrance in a white Rolls Royce.

“I was lucky. Chris’s band gave you that opportunity, man, to play with great people.”

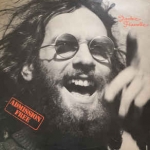

He released a solo album, ‘Admission Free’ in 1972. This came out of a friendship with Deke Arlon, a sometime associate of Joe Meek and fleeting Crossroads actor who would later steer the careers of Sheena Easton and Elaine Paige.

He released a solo album, ‘Admission Free’ in 1972. This came out of a friendship with Deke Arlon, a sometime associate of Joe Meek and fleeting Crossroads actor who would later steer the careers of Sheena Easton and Elaine Paige.

“Noreen made friends with him because he was an actor. I used to call him Million Dollar Deke because he has all these big time plans. But he pulled them off – with CBS and Chappell Music. He did become Million Dollar Deke. He took over a small record label from Yorkshire called York Records, which specialized in brass bands. He got an office in Carnaby Street and one of the first people he hired was Kenny Young. Within about six weeks they had a smash with Clodagh Rodgers (‘Come Back and Shake Me’). So that was them away. I used to hang about the office, it was good craic. He handed me a cassette, he says, take a listen, it’s a songwriter from America, you’ll like it. Tell me what you think – I’ve got a offer on the publishing. I went dead on… took it home. It was ‘Sweet Baby James’ by James Taylor. I listened to it about 200 times, I thought that’s fucking amazing. So I starting singing ‘Fire And Rain’ with the band and then we recorded it. It was nearly a hit. Would have been a hit only those fuckers (Blood Sweat And Tears) brought it out at the same time, but it was alright.

“He says, have you written any songs? I says aye, He says, let’s hear a few of them. So I let him hear a few, he says right, away and make an album. He says, spend as much as you like. So I hired all the best musicians in London and made an album. Henry McCullough, he only vaguely remembers being on it, God rest him. I met Henry coming out of The Ship in Wardour Street. He’d been rehearsing with Wings in the farm in Scotland. ‘I’ve been sent for messages,’ he said. He had a brown loaf (of dope) in his coat, supplies for the farm.

“So it’s not a great album but it was an album and it was mine. There’s not a note of jazz on it.”

Jackie returned to Northern Ireland in 1977.

“I had no plan. I got on the plane with a feeling of pain in my stomach and it took two years to get rid of it. Just came back doing an ordinary job, man. Was on the road selling TVs and hi fi.”

He became a presenter at Downtown Radio and took to journalism. There were other musicians to play with and return visits to the Barber Band, indefatigable jazz guys who never left the road. Jackie has also worked with the likes of Duke Special and more recently, Ciaran Lavery on his mini-album, ‘A King At Night – The Songs Of Bonnie Prince Billy’.

“I was so delighted to play with Ciaran Lavery, ’cause I knew that was my last kick of the ball – I just fuckin’ did. He rang me up and we went down to this tiny studio near Newry with Declan Legge. Very talented fella. Put the bass on these Bonnie Prince Billy songs. It was quite nerve-wracking in a way, because I’m not a session player on double bass man, you need to be really good like – orchestrally trained, really. But I got away with it, I’m on it and it sounds good.”

So, nearly 60 years on the road – does it give you a particular glimpse into the darker aspects of human nature?

“I love everybody, Stuart. More or less. I can’t think of anyone that I really hate. Even ones that do me down, I just laugh it off.”

And what advice do you give young musicians who want to go on the road. Should they join the circus?

“Well I tried to talk my grandson out of it and it didn’t work. It’s in the DNA. He’s away, man!”

Viva Flavelle. Bass notes, high times, fretless action.

Stuart Bailie

(Jackie Flavelle passed away 25 September, 2017. RIP)

Twitter

Twitter