It’s at the chill end of 2006 and I’m at Macfin near Ballymoney with Henry McCullough. It’s not exactly a country spread, but there’s a tidy porch out front and space behind for a few hens. Henry and his partner Josie look content as they fetch out tea for the guests and set more wood in the pot belly stove. It might be a rural scene from any number of places in County Antrim but we’re also in the company of a guitarist with an outstanding reputation, a master of tone and emotion, internationally travelled and feted.

It’s at the chill end of 2006 and I’m at Macfin near Ballymoney with Henry McCullough. It’s not exactly a country spread, but there’s a tidy porch out front and space behind for a few hens. Henry and his partner Josie look content as they fetch out tea for the guests and set more wood in the pot belly stove. It might be a rural scene from any number of places in County Antrim but we’re also in the company of a guitarist with an outstanding reputation, a master of tone and emotion, internationally travelled and feted.

Henry doesn’t labour his many achievements. The gold disc from ‘Red Rose Speedway’ on the wall behind him is the only totem from his rock and roll days. But that was quite a moment, as McCullough took up an offer from Paul McCartney, supporting the former Beatle back into live work with surprise college gigs, rough and resourceful. Still, McCullough was nobody’s pushover, and when Paul gave him a pre-arranged lead solo for the song ‘My Love’, the player refused. The orchestra was installed in the studio on an hourly rate but Henry insisted on improvising for the take. It was an audacious stand-off and yet McCartney gave way. Henry played off his wits and delivered a defining piece of surprise, lyricism and soul.

So there was old-fashioned, country thran in the character. And adventure also that had taken him out of Portstewart with the Skyrockets Showband at the age of 16, steering him to Woodstock some years after with Joe Cocker and the Grease Band, the only Irishman on that festival stage. And always the stories. Hurtling over Woodstock in an army helicopter, one of his colleages tripping horrendously on LSD and vomiting all over the flower children at Yasgur’s Farm.

For the past couple of hours we’ve been asking Henry about this rare existence for a BBC TV documentary, ‘So Hard To Beat’. Some of the best stories happen off camera, but hey, it’s the chance to hear about Janis Joplin and misbehavior at the Chelsea Hotel, about being signed to George Harrison’s record label and a great album that was spiked when George went into litigation over ‘My Sweet Lord’.

There were yarns about that rogue appearance on ‘Dark Side Of The Moon’ at Abbey Road, about folk sprees with Sweeney’s Men and a drug bust that hampered a session with Jimi Hendrix as producer. Opportunities and incidents and a descending blackness as the lifestyle went awry. There was the account of an overdose at the Fulham Greyhound, when he succumbed to heroin and ended up on the floor, beneath a table, under a coat. When his companions found him, he was blue and needing resuscitation. But then he was fixed up and presently McCullough was rocking again.

A low point was his return to Ireland around 1980 and a brutal incident with a breadknife that damaged tendons and almost ruined his capacity to play. When he did return, there was a severe kind of grace and a powerful, final period of his art. His voice was cracked and his used it sparingly. Likewise with the guitar. He had returned from some place other and he had the aura of Hank Williams, strung-out and dispossessed. To hear him sing ‘Lost Highway’ was an experience.

There were council housing blues in the Henry story before the happy outcome that brought him and his devoted partner to Macfin. It is there that we talk about mortality and the artist says that he’s not at all frightened, that he is prepared for the big sleep. You don’t disbelieve him. We rest for a moment before leaving and Josie puts on the most recent Paul McCartney album, ‘Chaos And Creation In The Back Yard’. The wood crackles in the stove and we say little. Josie mentions the pain in McCartney’s voice as his grieves for Linda again. Henry nods. We share a few seconds of empathy.

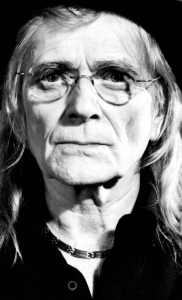

Henry McCullough, 1943-2016

Stuart Bailie

Photo by Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter