I’m at the door of Nina Simone’s dressing room and feeling apprehensive. We’re backstage at the HQ on Dublin’s Middle Abbey Street. It’s 7 October 1999 and the Hot Press Awards are just over. Sinéad O’Connor is around, wearing her priest outfit, nervy and talking plenty. Yet she is utterly quelled when Nina kisses her on the cheek. Many of the other Irish notables are nearby, including U2, The Corrs, Shane MacGowan, Westlife, and the emergent Snow Patrol. I’ve been interviewing them all for a BBC TV production and everything has gone well. Then it is suggested that we also speak to Nina.

Or Dr. Simone as she likes to be addressed. She has returned to Dublin because she’s been nominated in a special award – Guest Of The Nation. Other nominees are Elvis Costello, REM, Robbie Williams and David Gray. It’s an honorary gesture for an act that the island has embraced, and the Nina gig earlier in July at the Point had earned her a place on the list. Thus she was invited and sure enough, Nina flew in from her home in Bouc-Bel-Air. At first, I thought this was unusual, a proper soul-jazz diva, exiled in the south of France, making it over to Ireland for a night out. But during the evening, it transpires that Nina has rarely been awarded anything. Really. In her American homeland, she is perceived as a trouble maker and agitator. She’s not been back for many years, and the trophy shelf is not overly burdened.

Or Dr. Simone as she likes to be addressed. She has returned to Dublin because she’s been nominated in a special award – Guest Of The Nation. Other nominees are Elvis Costello, REM, Robbie Williams and David Gray. It’s an honorary gesture for an act that the island has embraced, and the Nina gig earlier in July at the Point had earned her a place on the list. Thus she was invited and sure enough, Nina flew in from her home in Bouc-Bel-Air. At first, I thought this was unusual, a proper soul-jazz diva, exiled in the south of France, making it over to Ireland for a night out. But during the evening, it transpires that Nina has rarely been awarded anything. Really. In her American homeland, she is perceived as a trouble maker and agitator. She’s not been back for many years, and the trophy shelf is not overly burdened.

So she attended the awards ceremony, sitting in a magnificent throne of carved mahogany, all elegant fretwork and sure presence. Nina looked beatific and strange, like something off an old hieroglyphic. She was beyond all of our experiences, growing up Eunice Kathleen Wayman in Tyron, North Carolina, showing enormous musical promise but constantly rebuffed and exploited. She’d become political in 1963 after the murder of Medgar Evers and the killing of four girls in Birmingham, Alabama. She’d written ‘Mississippi Goddam’ about the segregated south and thereafter her music was often spikey, contemptuous and sore.

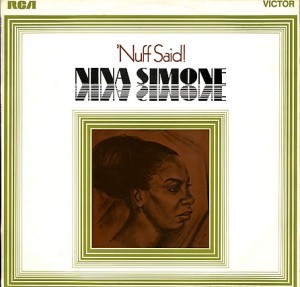

At her Point Depot gig on 24 July, Nina’s set had included ‘Why? (The King Of Love Is Dead)’ a eulogy for Martin Luther King. The first time she had performed this was at the most extraordinary concert on 7 April 1968, just three days after the assassination of MLK. The night was recorded and parts of this appeared on an album called ‘’Nuff Said’. You can hear Simone at the Westbury Music Fair, consumed by sorrow, rage and paranoia. The Long Island audience is offering comfort and also feeling the anguish while Simone pulls out some of her most severe sentiments. The MLK tribute had just been written by her bassist Gene Taylor and rehearsed for the first time the previous day. As the concert progresses, ‘Why? (The King Of Love Is Dead)’ becomes a 12 minute centerpiece, a song that moves from a wondrous dream to a heinous end. “They’re shooting us down, one by one,” she remarks.

I’m thinking about all this as I stand by her dressing room with the TV crew. However, Nina also has a resourceful manager called Clifton, who wants a word with the BBC exec. They retire to a quiet corner, terms are discussed, hand gestures are large and important notes are scribbled on paper. While I don’t get to know the detail, my understanding is that the artist is to be rewarded for her time and her legendary status. The interview will not last long and there will be terms and conditions for the TV use. All of this is thrashed out in a couple of minutes but the context is dramatic and the pressure is emphatically on.

Now is my time to meet Dr. Simone in this small room. She smiles, but the eyes are remote. On the table is the trophy she has just collected – designed by John Rocha, as I remember. I can’t recall the champagne that she had been supplied with. Her preferences being Cristal and Dom Perignon, but she might tolerate Moët. Whatever, she’s just recently filled the rosebowl award with champagne and then drank all the contents through a straw.

It’s not the best interview ever. The small talk is painful, although she is sincerely moved by the award and by the idea of Ireland caring enough to bring her back here. Evidently it’s a moment for her also, and the smiles mean it. We skim though her career, the prodigious start, the career frustrations with the Curtis Institute and the Juilliard School Of Music in New York. She says enough, but the story is well-worn. So too is the song writing royalty issue that gave her little reward when a Chanel ad took ‘My Baby Just Cares For Me’ to the top of the charts.

Her jewelry and make-up deliberately accent the impression of royalty, a persona she has cultivated over the decades to ward off the freeloaders, the back-biters and the gawpers. But the conversation lifts a little when we discuss her time around the bars of Manhattan, when she brought her aspirations low just to pay the rent and to finance an education. I mention her supposed friendship with Brendan Behan and sure enough, they were pals in those lost years. The playwright with his small feet and his vast store of Irish ballads. And just for a second I’ve got her delighted and engaged. She used to sing ‘Danny Boy’ with Brendan late into the night. Maybe it was Village Gate or The White Horse Tavern, I don’t get the chance to ask. Wherever, it earned them a few dollars and it lifted the pain a little.

My time with Nina Simone is over. I’ve been perspiring, emotionally done. Normally I can manage an interview situation, but my subject is too far out there and the context has been fraught. Before I am out the door, she’s into her own zone again and a heavy fatigue settles around her. A legend, not much farther to go. Less than four years from now and her trials will all be over.

Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter