Bill Kirk by Stuart Bailie

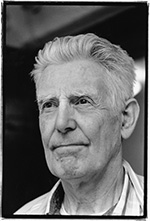

Bill Kirk is 88 and alert. He has a gracious style that has informed so many excellent photos of Belfast. He has walked the lesser-known parts of the city, noting the dereliction and neglect. Mostly though, his camera finds light in the human faces and gestures.

His film archive amounts to over 20,000 images plus an ongoing collection of digital pictures. It’s an immense resource, showing us slum clearance, conflict, a gun-toting wedding, a bishop, a bookie, city barbers, Irish pipers and street drinkers.

That’s a Bill Kirk picture on the sleeve of the last David Holmes record, Blind on a Galloping Horse. It was taken on bonfire night at the corner of Napier Street, 1974. As the two people embrace beside the flames, the space between them traces out the curves of a heart.

Photo by Bill Kirk c/o Belfast Archive Project

Bill’s work remembers the street corner newsagents, stacked up with Embassy Regal and Gallaher’s Blue. He pictures the youth culture – punk rockers at the Harp Bar, skinheads on Chapel Lane and scooterists with their Vespas at Wellington Place. He has invested his time at civil rights marches, union rallies and bomb damage sales.

Skins on Chapel Lane. Photo by Bill Kirk c/o Belfast Archive Project

Born in Newtownards in 1937, he began documenting his family with a Felica camera that he had purchased in Drogheda in 1958. Ten years later, he discovered a new UK publication called Creative Camera, edited by the revolutionary eye of Bill Jay and published by Colin Osman.

This was a place to learn about photographers like Robert Frank, who had reviewed an entire, messy nation in his seminal book, The Americans. Bill Kirk was also moved by the work of Lewis Hine, who had documented rural poverty, immigration and the Great Depression in the USA. His empathetic work helped to bring about the end of child labour there.

“When I started to read Creative Camera,” Bill tells me, “It had a profound influence on me. At that same time, I had been a member of a [camera] club, and it only got through to me on the late 60s how trite and how hackneyed all the club stuff was. Creative Camera just alerted me. It brought people like the great American documentarians to my attention. Men like Lewis Hine, who said, ‘There are two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated.’ It was a shock to see strong, meaningful stuff. But a purpose was brought in.”

Moore’s, Little Patrick St. 1974. Photo by Bill Kirk c/o Belfast Archive Project

Much of his life changed in 1971. He was made redundant from his position as a draftsman at Short Brothers. He was also diagnosed with tuberculosis, the infectious disease that had taken his parents, Nora and Bill, at a young age. He lost a kidney and recuperated for six months at Foster Green Hospital by the Saintfield Road. Physically, he was resilient. He had built up his strength over many years with a regimen of long-distance cycling, a practice he continued until two years ago.

“When I had finished that,” Bill remembers about the impact of 1971, “I actually said to myself, if I can do that, I can do anything. Although I felt quite troubled, I felt that confidence somewhere inside me, There was something that would work out OK. So, I went along to the College of Art, to begin getting a batch of work together. Although I wanted to take heed of my lecturers, I had this urge to document what was going on in front of my very eyes.”

Raglan St. Photo by Bill Kirk c/o Belfast Archive Project

Bill had already been making photographs of Belfast as the conflict began.

“In the early period of the struggles, particularly 1969, when the awful attacks happened – that drew me and shocked me into realising that it was almost a duty for anyone that was half-knowledgeable, to take some move towards trying to understand it at least, in images.

“I went up the Falls Road to see the burnings that took place. ‘The Pogroms’, as they’re referred to. And it sort of enlightened me. I had been a political thinker anyway. I desired a sane-thinking country, and it didn’t appear.”

Just ahead of his departure from Shorts Brothers, a colleague called Davy Moore had recommended a novel called The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists. This was another critical introduction, a book by Robert Tressell (aka Robert Noonan) about the exploitation of house painters and signwriters in Mugsborough, based on the town of Hastings. The book was published in 1914, three years after Noonan had died from tuberculosis. It was a moving depiction of brute capitalism and the abuse of the poor. This call to socialism was widely read in the trenches during World War I and keenly praised by the likes of George Orwell, Tony Benn and Brendan Behan.

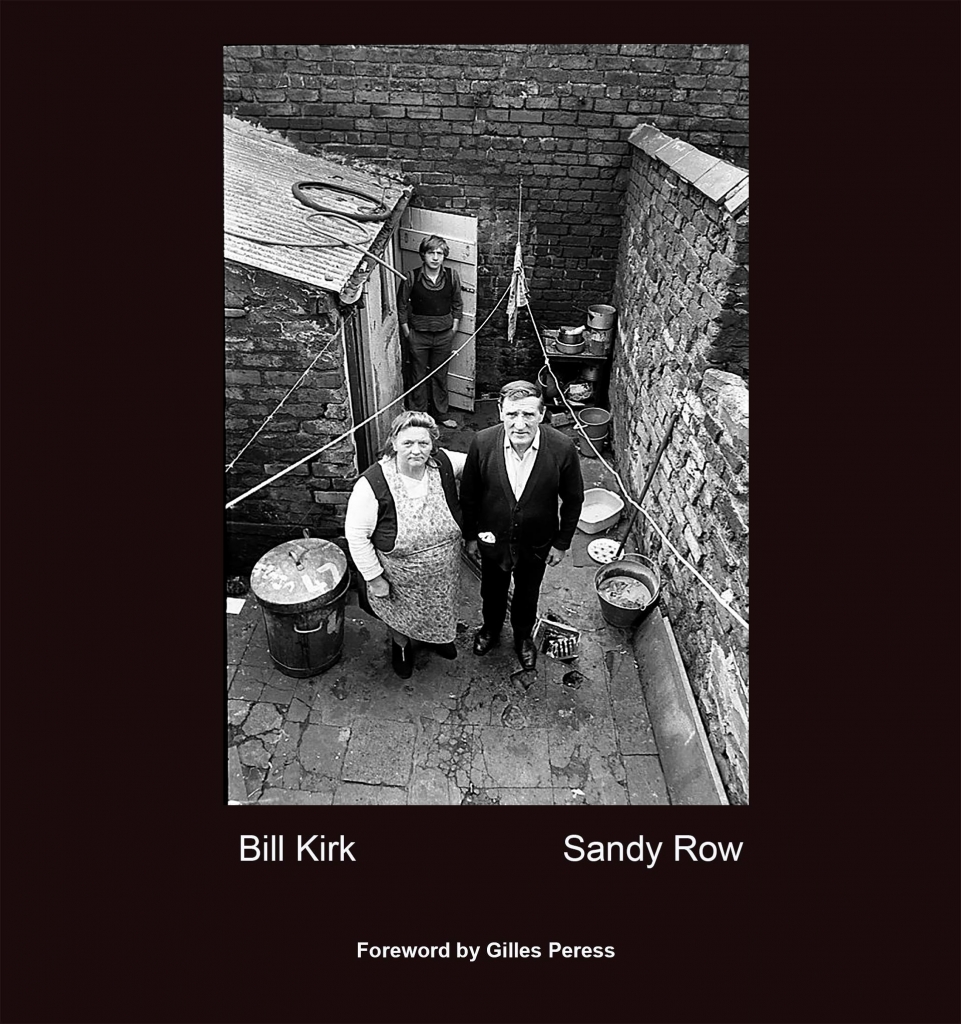

Mrs Elliott and family by Bill Kirk.

So while Bill was at the Art College, he committed himself to spending time in areas of deprivation nearby.

“I was drawn into the situation of Sandy Row. I discovered that there was going to be a major redevelopment. This came to light for me in 1973, when I had two years completed at the college. So along with a Derry man, Arthur Watson, we set about doing photography which the Arts Council exhibited for us (Ulster Photographs) before we had finished our course.

“Why I did the Sandy Row project was that I was a really troubled guy. During that shoot, I met the now-renowned Gilles Peress (French photographer with the Magnum Photos agency) on Sandy Row. He was a guidance to me in many ways, without realising. He was saying to me things like, ‘look a bit happier’. I must have conveyed with my body language, that I was a troubled person. And he says, ‘you think too much’.

“Looking back, I see the actual image that I took while in his presence, was like a step forward for me. There’s a shot of two shopping ladies in identical white coats. He was at my shoulder, right beside me, when I took that shot. I was acting like what he was suggesting – ‘don’t think too much’.”

Sandy Row, 1974. Photo by Bill Kirk c/o Belfast Archive Project

Bill took a job at the Tourist Board, active with his Olympus OM camera and medium format gear, trying to find the good in a place under duress. Some of his peers thought he might have been misguided.

“The powers that be in the art world looked at me at little bit critically, because I had taken a job, trying to promote tourism. But I still wanted to stay close to documentary. The whole process of working at the Tourist Board actually refined my practice so much. My simple skills with the camera improved. So, the pictures were admired pretty widely. I was really pleased with that.

“I saw myself leaving Bangor where we lived at the time, coming to Belfast and saying to myself, ‘OK, show me your secrets’. Which sounds a bit pretentious, but it was actually an urge within me.”

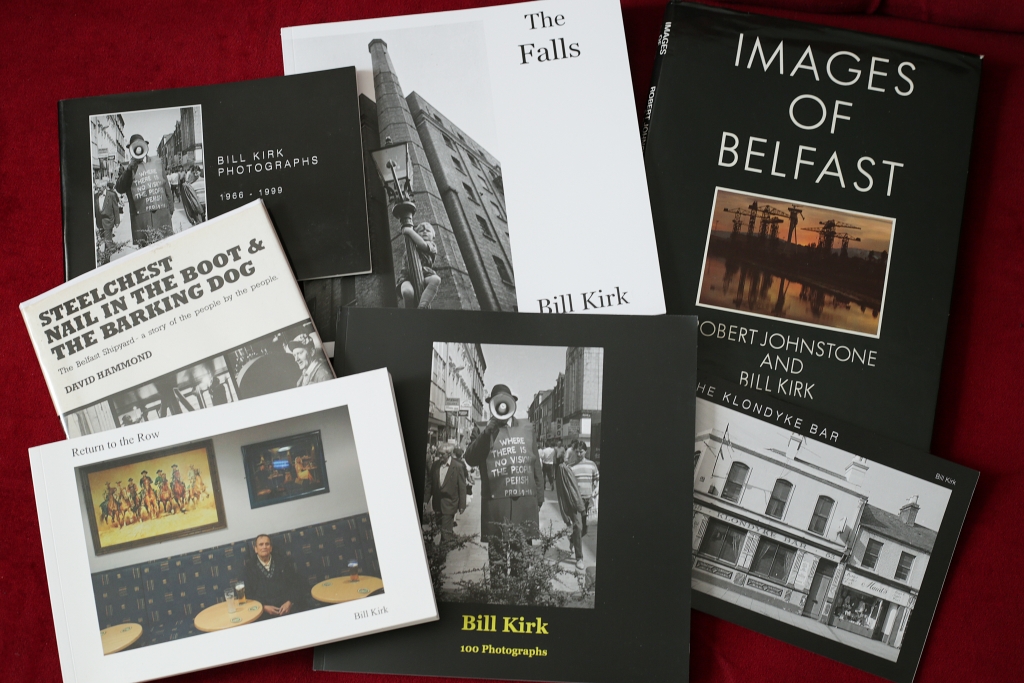

His exceptional work includes The Klondyke Bar (1975, reprinted 2011), Images of Belfast (with writer Robert Johnstone, 1983), Steel Chest, Nail in the Boot and the Barking Dog (with film maker David Hammond, 1986) and Return to the Row (2019). Bill’s collection is now supported by Frankie Quinn and the Belfast Archive Project. New parts of the story are being revealed, including his work around the Pound Loney – The Falls (2024).

His exceptional work includes The Klondyke Bar (1975, reprinted 2011), Images of Belfast (with writer Robert Johnstone, 1983), Steel Chest, Nail in the Boot and the Barking Dog (with film maker David Hammond, 1986) and Return to the Row (2019). Bill’s collection is now supported by Frankie Quinn and the Belfast Archive Project. New parts of the story are being revealed, including his work around the Pound Loney – The Falls (2024).

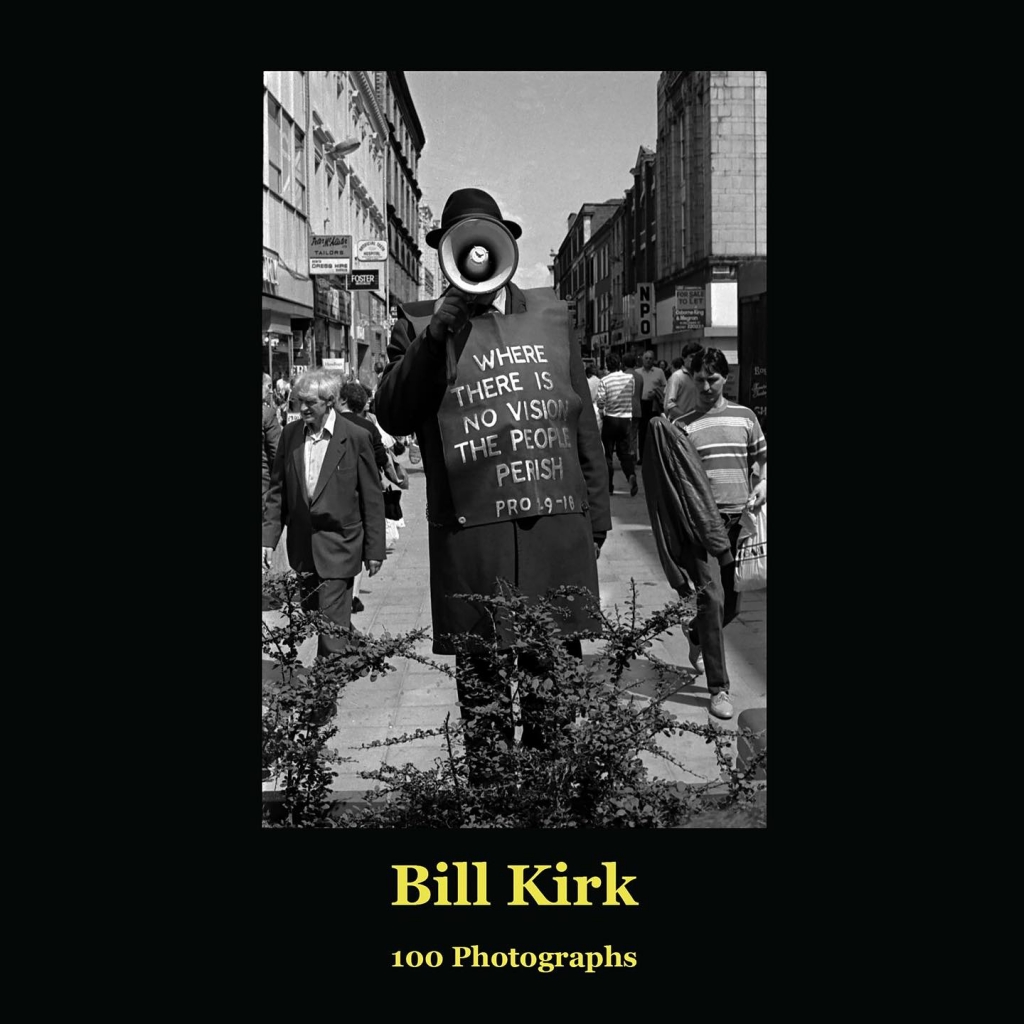

The Ulster Museum is currently hosting The Bill Kirk Archive Exhibition, featuring 100 of his images, some of them previously unseen. This is accompanied by a book, Bill Kirk: 100 Photographs.

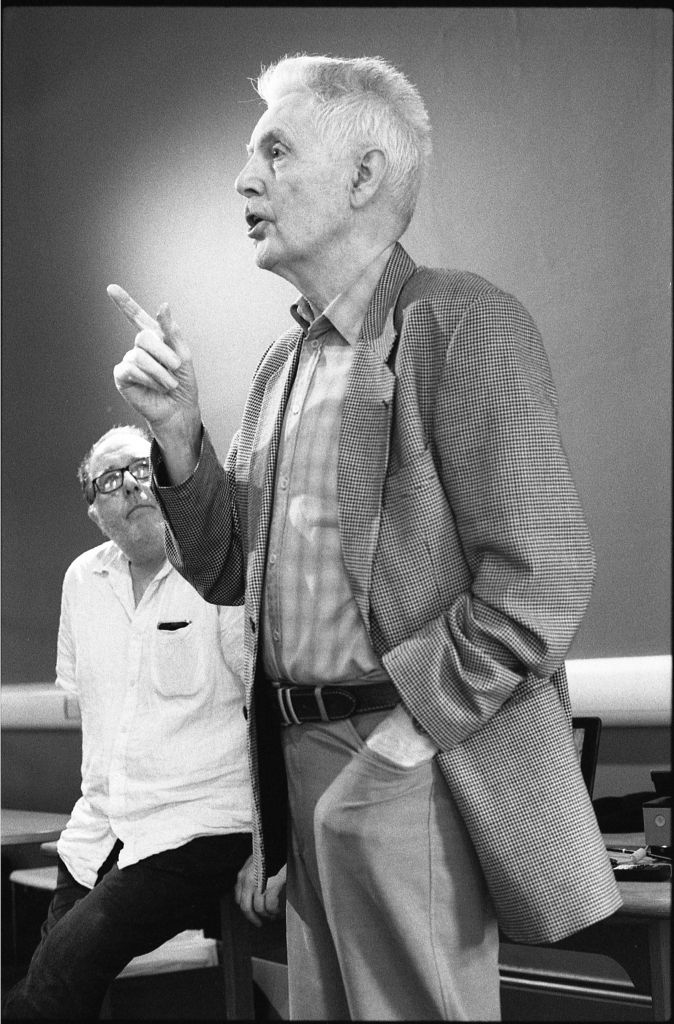

Bill Kirk (foreground) with Frankie Quinn, 2024. Photo by Stuart Bailie

I ask Frankie, who curated the exhibition, if Bill is up there with the significant Irish photographers.

“Absolutely. He’s up there, yeah. He has his own style that you can identify – that’s a Bill Kirk. He would underexpose and then overdevelop slightly. You get the whole technical range. He was highly technical. He also used to review cameras for Camera Weekly.

“And there’s his empathy. His character gets him in places – a big gentleman. You know, you have to get people’s confidence before you let them take your picture, and Bill does it. He has it. And his politics was driving him too. He quoted Mrs. Elliott from the Sandy Row.: she says to him, ‘show what the landlords do to us, son’. He compared her to ‘Ma’ in Steinbeck’s the Grapes of Wrath.”

One of the most iconic of his pictures is the evangelist in Ann Street, his face obscured by his megaphone – a speaker horn with a hat perched over it. But what makes it truly great is the message on the man’s vest, a Bible quote from Proverbs 29:18.

One of the most iconic of his pictures is the evangelist in Ann Street, his face obscured by his megaphone – a speaker horn with a hat perched over it. But what makes it truly great is the message on the man’s vest, a Bible quote from Proverbs 29:18.

Bill considers the moment that led to this picture. Some might call it a ‘decisive moment’, a brief instance when the world takes on an extra layer of meaning. He smiles.

“Things like coming across a street preacher, with a legend on his chest saying, ‘Where there is no vision, the people perish’ – I looked at it as being lucky, just happenstance. But others tried to convince me that, no, there’s no luck in that, Bill. You found that.”

Stuart Bailie

(The Bill Kirk Archive Exhibition is at the Ulster Museum until June 1. Information here)

Twitter

Twitter