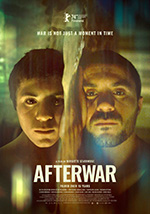

Afterwar is a film about street kids in Kosovo, selling peanuts, phonecards and cigarettes in late-night bars. These phantom children work the tables and the last of the dawn trade before taking their bus rides out of Pristina. They return to the rural beyond, to damaged homes and bleak landscapes. Parents are dead, injured or missing. Here it is, the dispossession of war.

Afterwar is a film about street kids in Kosovo, selling peanuts, phonecards and cigarettes in late-night bars. These phantom children work the tables and the last of the dawn trade before taking their bus rides out of Pristina. They return to the rural beyond, to damaged homes and bleak landscapes. Parents are dead, injured or missing. Here it is, the dispossession of war.

Another recent film release, Kneecap, is about two rappers from West Belfast and a DJ from Derry. Their lives are feverish and messy, cranked up on cocaine, ketamine and Buckfast tonic wine. Their renegade style of hip-hop brings fresh energy to the Irish language and excites their listeners. Now these self-styled ‘Republican hoods’ have become successful but still, there’s a stray note of anxiety in the mix.

They take time out of the film to explain. Kneecap, they tell us, are affected by the 30-year conflict in the north that left over 3,500 dead. Their parents saw the worst of it, but the hurt has travelled onwards since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. They say it is transgenerational trauma. Some medical theories suppose that the condition is inherited through DNA, but others dispute this. Whatever, the Kneecap community knows plenty about mental health problems, fractured families and substance abuse.

They take time out of the film to explain. Kneecap, they tell us, are affected by the 30-year conflict in the north that left over 3,500 dead. Their parents saw the worst of it, but the hurt has travelled onwards since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. They say it is transgenerational trauma. Some medical theories suppose that the condition is inherited through DNA, but others dispute this. Whatever, the Kneecap community knows plenty about mental health problems, fractured families and substance abuse.

The Afterwar film follows a trail of distress through the personal stories of Shpresim, Xhevahire, Gëzim and Besnik. The project started as a short documentary, Out of Love in 2009, on the tenth anniversary of the Kosovo-Albanian war with Serbia (13,000 dead, over 800,000 evacuated, 20,00 rape victims). Danish director Birgitte Stærmose has returned to her subjects for this full-length update, spanning 15 years.

Afterwar uses supporting actors alongside these authentic characters. The action combines real-life footage with more scripted scenes. Stærmose insists that this was a collaboration with the cast. Not everyone approves: some of the local audience at the Dokufest showing in Prizren, Kosovo felt uneasy with this development. Certainly, the ending seems overly pessimistic. The most captivating parts of the film happen when the dramatic fourth wall comes down and these individuals speak directly to the viewer. “When war ends, men get quieter,” is one line. Also: “You think the war is over. I am just waiting for this afterwar to end.”

Afterwar uses supporting actors alongside these authentic characters. The action combines real-life footage with more scripted scenes. Stærmose insists that this was a collaboration with the cast. Not everyone approves: some of the local audience at the Dokufest showing in Prizren, Kosovo felt uneasy with this development. Certainly, the ending seems overly pessimistic. The most captivating parts of the film happen when the dramatic fourth wall comes down and these individuals speak directly to the viewer. “When war ends, men get quieter,” is one line. Also: “You think the war is over. I am just waiting for this afterwar to end.”

Gëzim Kelmendi has intense soul in his eyes. The cinematography may be gloomy and artful, but his resilience will not be dimmed. He finds some joy in fatherhood and wants to beat the limits of class, race and illiteracy. And then, without ceremony, he starts to rap, spilling bars and rhymes about his difficult world. Just like his Irish counterparts, he has found a voice and a method. You want to stand up and cheer.

Gëzim Kelmendi has intense soul in his eyes. The cinematography may be gloomy and artful, but his resilience will not be dimmed. He finds some joy in fatherhood and wants to beat the limits of class, race and illiteracy. And then, without ceremony, he starts to rap, spilling bars and rhymes about his difficult world. Just like his Irish counterparts, he has found a voice and a method. You want to stand up and cheer.

With Kneecap, Director Rich Peppiatt has wisely decided to serve their wit and subversion. They are amusing when they might be serious and savage when it’s not expected. Importantly, Peppiatt introduces Michael Fassbender as Móglaí Bap’s missing father Arlo and sets him up for a moody reckoning. The film cannot end until history, the warrior mythology and the patriot dead are all given their moment.

At the end of any modern conflict there is often talk of a ‘peace dividend’. Unfortunately, the prize-winners tend to be property developers and gentrifiers. Poor people on the fringes may see no benefit at all. That’s a common message with Afterwar and Kneecap. Makes you wanna holler.

Stuart Bailie

Read the review of the Kneecap album here.

Twitter

Twitter