Steve Pyke takes astounding photos of faces and hands, landscapes and astronauts. He has pictured war veterans, roadside shrines, monumental thinkers and the countenance of Shane MacGowan.

Steve Pyke takes astounding photos of faces and hands, landscapes and astronauts. He has pictured war veterans, roadside shrines, monumental thinkers and the countenance of Shane MacGowan.

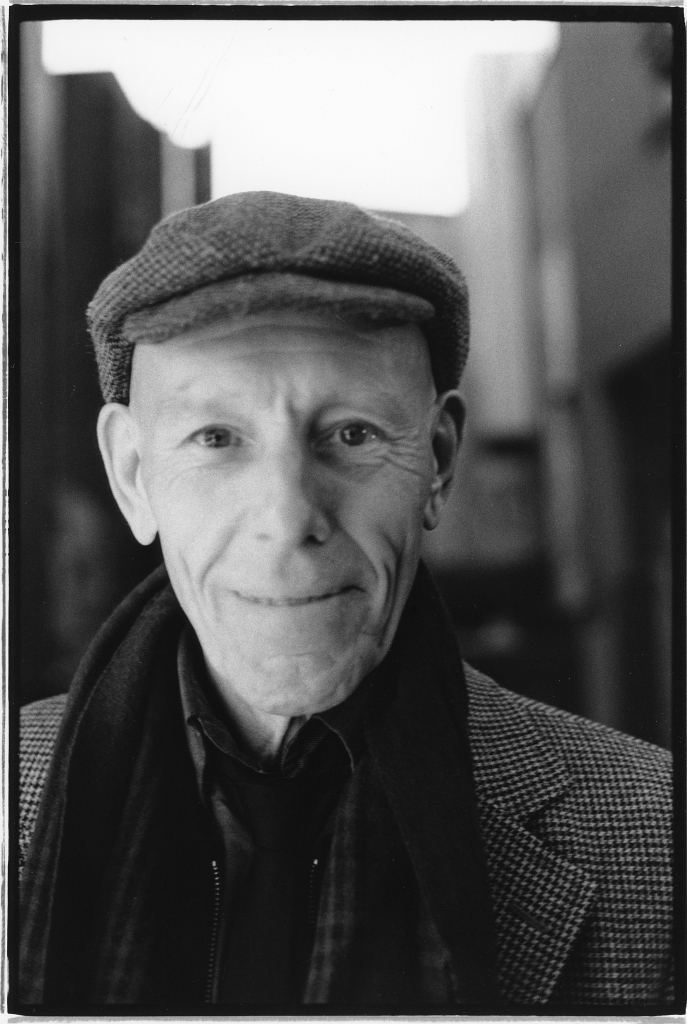

An artist and an agent of mischief, he takes most of his portraits on a Rolleiflex TLR that was engineered in 1957 and still delivers detail, skin tones and fine poetry on silver halide. For many sittings, he spends a lot of the scheduled time talking with his subjects, finding a sympathetic rhythm. Then he gets in tight with close-up lenses and aims for the moment of transference when his sitters reveal a piece of their soul.

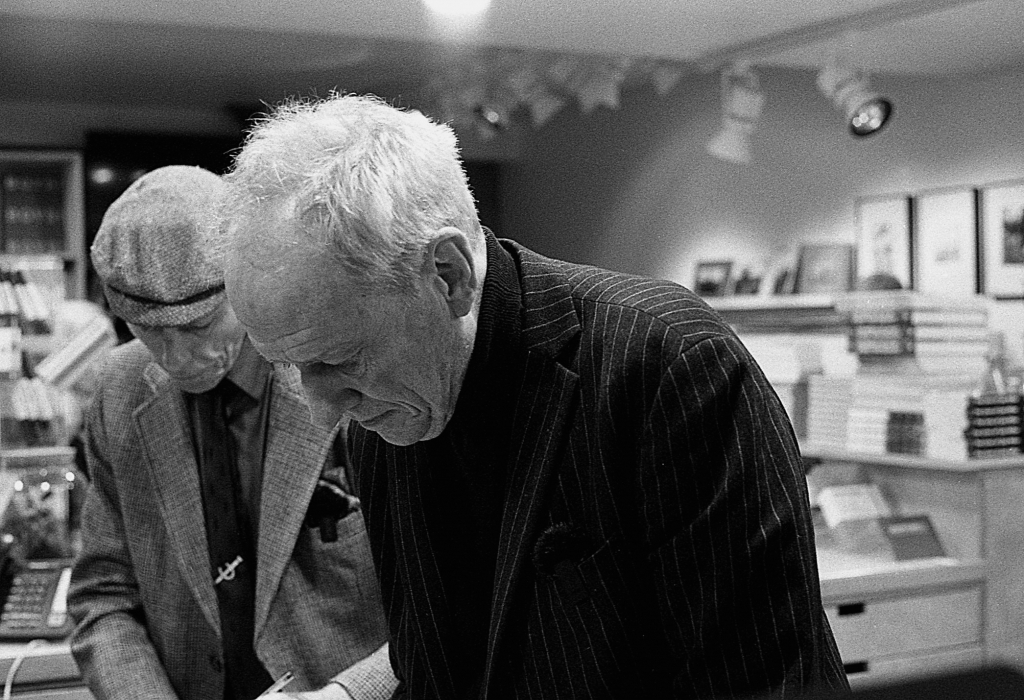

Steve Pyke, Dublin 23.02.24. Photo by Stuart Bailie

Earlier in life, Steve had been a teenage motorcycle racer and then a vocalist with Leicester punk group, the RTR’s. A mate loaned him a camera and he started taking images of The Clash and the Subway Sect. He was commissioned by the NME and The Face. More recently Steve was a staff photographer for the New Yorker, following on from the late Richard Avedon in 2004.

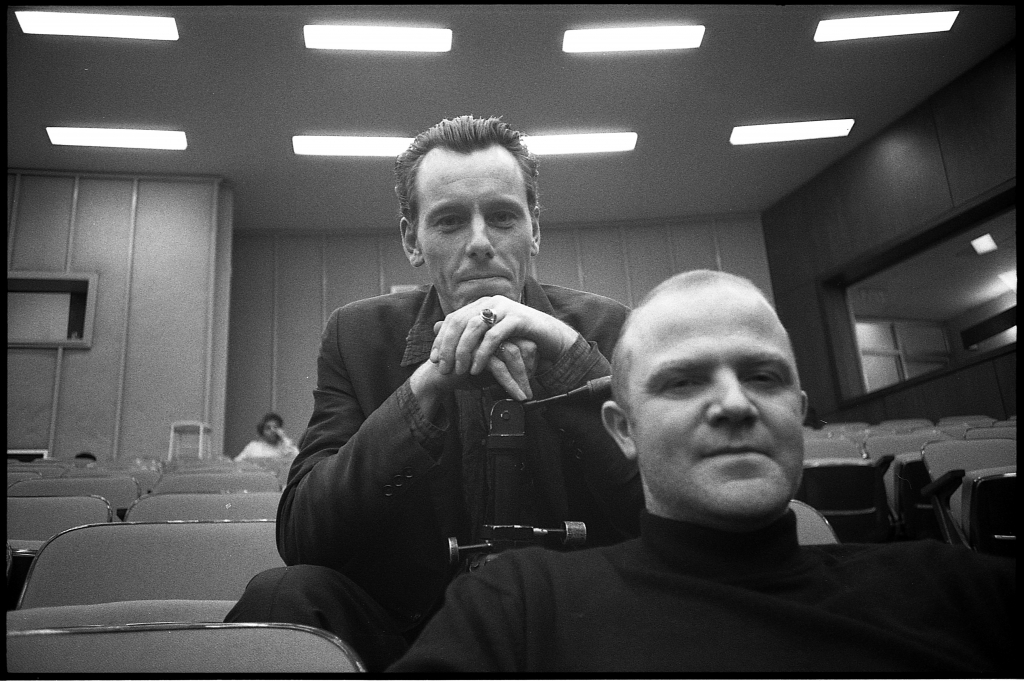

I first met Steve around 1988 when we both worked at the NME and there was no shortage of wayward faces. We travelled to Beirut in December 1991 to cover a gig with a French band, Les Negresses Vertes – the first visiting act there for 20 years. The city was jumpy and Hezbollah was active. Several foreign hostages were still being held captive, chained up in basements. The sense of dread from an awful conflict persisted.

On the last night of the visit, we sat on the roof of a damaged hotel with the band’s singer Helno. Just like Shane MacGowan, he had been born in Christmas day. He also had a sweet smile and a predilection for the dark stuff – he died of a heroin overdose in 1993. As we talked and drank, Helno obliged us with a rendition of Shane’s infernal cackle. Steve and I laughed. Presently, a dramatic moon was gleaming and we looked over the Lebanese shoreline that was beautiful despite everything. We were stressed and confused. So, we stood up and literally barked at the moon.

Steve Pyke and Stuart Bailie, American University of Beirut, 1991

I saw Steve at the King’s Hall in Belfast with Nirvana in 1992 and I wrote about those scenes in another blog here. Kurt was hospitalised later that evening. Steve’s pictures show a band in disarray and a singer who was terminally weary. Cobain gave a few more resonant frames to the Pyke catalogue.

Steve Pyke with Buzz Aldrin from the astronaut project, Moonbug

Mark E Smith, Frenz

Strangely, there’s never been a book of Steve’s music portraits. He has memorable images of Iggy, Keith Richards, Bjork, David Byrne, Lee Perry and Mark E. Smith. A selection is in the planning stages. Pyke enthusiasts have been content with a series of other collections. Notably, his studies of the astronauts who walked on the moon (documented in the 2011 film Moonbug) and two volumes titled Philosophers, including Noam Chomsky, Karl Popper, EP Thompson and Isaiah Berlin. Major intellect, wiry facial hair, unflinching regard.

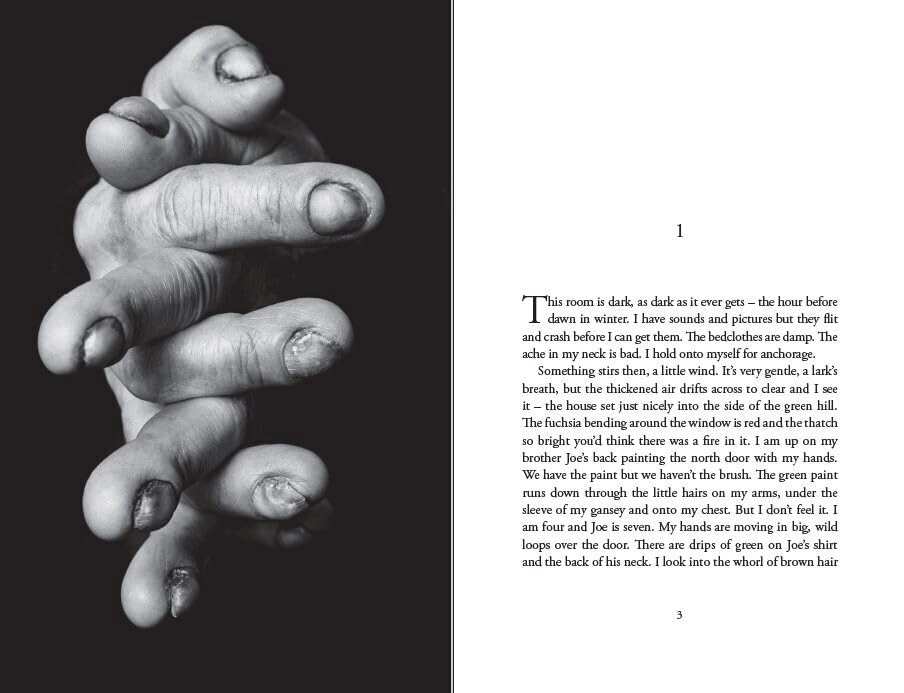

Steve was working with Iris Murdoch in 1990 when he showed her a box of photos that he had been taking in Ireland since 1979. She recommended them to a publisher, which eventually resulted in a brilliant book, I Could Read the Sky.

The project took a messy route before a publishing date of 1997. At one point there was pressure to make a tourist hardback called Ireland, which was resisted. A positive move was to partner Steve with the Chicago-born author, Timothy O’Grady, who had recognised his emigrant roots in a debut, Motherland. The latter’s reaction to the Pyke images was to create a work of fiction, the story of an Irishman, displaced from the Atlantic coast, labouring in England. He takes his solace in drink and memory:

The project took a messy route before a publishing date of 1997. At one point there was pressure to make a tourist hardback called Ireland, which was resisted. A positive move was to partner Steve with the Chicago-born author, Timothy O’Grady, who had recognised his emigrant roots in a debut, Motherland. The latter’s reaction to the Pyke images was to create a work of fiction, the story of an Irishman, displaced from the Atlantic coast, labouring in England. He takes his solace in drink and memory:

‘What I could do. I could mend nets. Thatch a roof. Build stairs. Make a basket from reeds. Splint the leg of a cow… Read the sky… Tend bees. Bind wyndes. Make a coffin. Take a drink. I could frighten you with stories. I knew the song to sing to a cow when milking. I could play 27 tunes on my accordion.’

Timothy’s story was partly based in conversations in north London bars, in meetings with ex-pats at the Camden Irish Centre and the Roger Casement Centre in Archway. The fiddle player Martin Hayes suggested some of the tunes that might soundtrack it. The result is occasionally sweet and lyrical, but of course it aches like a Pogues song.

The book was formatted so that the text and Pyke’s grayscale images seemed to converse with each other. It made good use of suggestion and recall. Later, I found that one inspiration had been A Fortunate Man by John Berger and photographer Jean Mohr, the study of a compassionate GP from the Forest of Dean. Fittingly, Berger wrote a foreword for I Could Read the Sky. “Here is a book of tunes without musical notes,” he noted.

The book was formatted so that the text and Pyke’s grayscale images seemed to converse with each other. It made good use of suggestion and recall. Later, I found that one inspiration had been A Fortunate Man by John Berger and photographer Jean Mohr, the study of a compassionate GP from the Forest of Dean. Fittingly, Berger wrote a foreword for I Could Read the Sky. “Here is a book of tunes without musical notes,” he noted.

The book was rightly praised and it prompted a film (with Dermot Healey, directed by Nichola Bruce, who also made Moonbug) plus concert dates with Martin Hayes, Dennis Cahill, Sinéad O’Connor and Iarla Ó Lionáird, who released an album in response, via Real World Records.

I Could Read the Sky has continued to reach people. Robert Macfarlane calls it “a masterpiece”. Old copies with the Harvill Press imprint are valued, particularly the large format version, the better to see Steve’s images. Then in 2023, there was a fresh edition by Unbound. There were extra photographs and a new sequencing, plus a haunting audiobook with music by Martin Hayes.

I Could Read the Sky has continued to reach people. Robert Macfarlane calls it “a masterpiece”. Old copies with the Harvill Press imprint are valued, particularly the large format version, the better to see Steve’s images. Then in 2023, there was a fresh edition by Unbound. There were extra photographs and a new sequencing, plus a haunting audiobook with music by Martin Hayes.

Steve now lives in New Orleans but I met him recently in Dublin, at the Photo Museum Ireland. Choice images from the book are on the gallery wall. Three generations of women on Inishmaan plus guys throwing the bullet in County Cork. Fast times in Funderland and bonfire night in Belfast. A wet field in Donegal. At the launch event, we heard Timothy reading from the book while Iarla Ó Lionáird and Cathy Jordan sang into the evening chill. A privilege.

Steve Pyke and Timothy O’Grady, Dublin 23.02.24. Photo by Stuart Bailie

England puts other refugees to work now, and those Irish testimonies have a phantom quality. I Could Read the Sky evokes old patterns and manners. You respond to the faces that looked so openly into Steve’s lens. An important remembrance, significant art.

Stuart Bailie

I Could Read the Sky is at Photo Museum Ireland until 16 March 2024.

See a gallery for Steve’s book images on the Guardian website here.

Twitter

Twitter