Cathal McNaughton walks through the documentary I Dream in Photos with a fragile, abstracted air. He tugs often at the fraying bill of his baseball cap. With his beard and denim shirt, he looks like a wayward act from Domino Records. He has a severe story to share with you.

Cathal McNaughton walks through the documentary I Dream in Photos with a fragile, abstracted air. He tugs often at the fraying bill of his baseball cap. With his beard and denim shirt, he looks like a wayward act from Domino Records. He has a severe story to share with you.

As a documentary photographer, he had travelled through conflict zones and scenes of major horror. His profile rose when he sent back images from the Rohingya crisis in 2017. The civilians were fleeing persecution in Myanmar and Cathal met them across the border in Bangladesh. He pictured the mass anxiety, the mothers with their dying infants. Cathal was true to his remit. He let us see an attempted genocide.

He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, alongside his colleagues at the Reuters news agency. Because of the narrative, he was also refused entry back to his working base in India. And so this documentary film finds Cathal, returned to East Antrim, renovating a cottage on the slopes of Mount Lurigethan. He chips back the old wall plaster and rummages in packing cases. This is where the trauma gets processed.

He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, alongside his colleagues at the Reuters news agency. Because of the narrative, he was also refused entry back to his working base in India. And so this documentary film finds Cathal, returned to East Antrim, renovating a cottage on the slopes of Mount Lurigethan. He chips back the old wall plaster and rummages in packing cases. This is where the trauma gets processed.

It’s an occupational difficulty that has previously damaged photographers like Don McCullin and Sebastião Salgado. In the case of Kevin Carter, the impact of his pictures was personally unbearable. But Cathal is fixing up family life, in parallel to the building repair. He literally has no cameras to work with. Restoration follows and by the end of the film, there’s an agency job offer and a tentative restart.

I Dream in Photos, co-directed by Gary Lennon and Ollie Aslin, has a world premiere at the QFT in Belfast, one of the many remarkable moments in the Docs Ireland festival programme. There is a similar theme with Tish, a remembrance of the late photographer Tish Murtha, who was essentially crushed by state policies. Her Tyneside images of family, street urchins and resilient fun are witness to an era that reached from the time of Margaret Thatcher and beyond the workings of Tony Blair. The miners’ strike had been broken and the north-east was priced down for decline.

Photo by Tish Murtha

Her work had defiance and soul, especially the Youth Unemployment set. In an interview for Newport College of Art, Tish told David Hurn, “I want to take pictures of policemen kicking children”. That was chiefly her mission until she died of a brain aneurism in 2013, poor and under-valued. The film, directed by Paul Sng and presented by her daughter Ella, is an emotional recall. We see the hollowed-out faces of Tish’s surviving brothers and sisters and realise the cost of a mean, relentless class war.

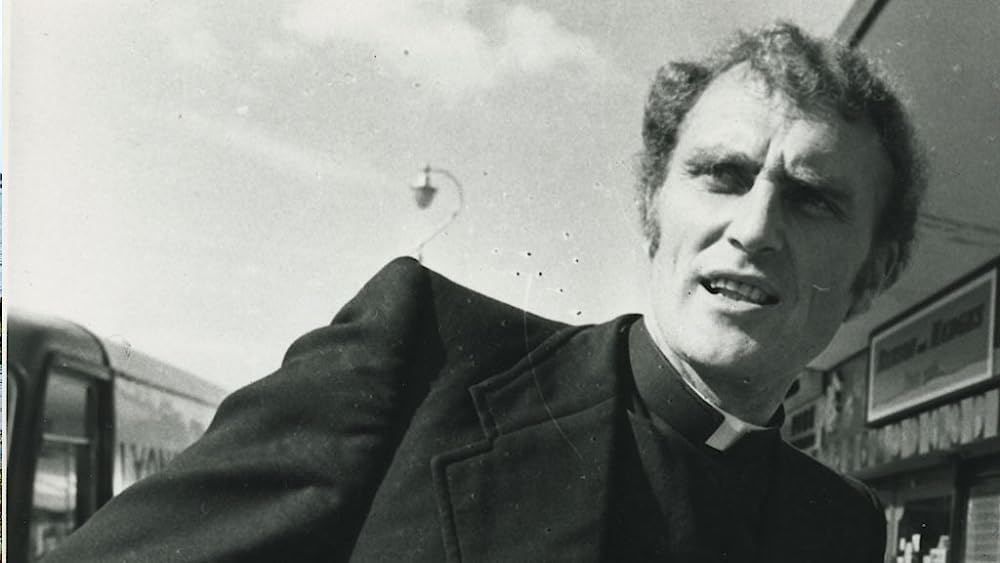

Alison Millar finished the beautiful Lyra in 2021 and the rolling acclaim has prompted some retrospective showings for Docs Ireland. The Father, the Son and The Housekeeper is a 2007 study of Michael Cleary, the rogue priest, showman and chancer. Alison had filmed him at home in 1991, unaware that the housekeeper’s son was also Michael’s own. With hindsight, this footage is endlessly brazen. Cleary had figured that a puff of incense and piety would delude religious Ireland and let him indulge, even delivering sex education lessons to blushing schoolgirls. The ruse worked until his death when the story broke. Alison returned to her footage afterwards, regaining the confidence of Ross the son and disassembling the act of a clerical con job.

Alison Millar finished the beautiful Lyra in 2021 and the rolling acclaim has prompted some retrospective showings for Docs Ireland. The Father, the Son and The Housekeeper is a 2007 study of Michael Cleary, the rogue priest, showman and chancer. Alison had filmed him at home in 1991, unaware that the housekeeper’s son was also Michael’s own. With hindsight, this footage is endlessly brazen. Cleary had figured that a puff of incense and piety would delude religious Ireland and let him indulge, even delivering sex education lessons to blushing schoolgirls. The ruse worked until his death when the story broke. Alison returned to her footage afterwards, regaining the confidence of Ross the son and disassembling the act of a clerical con job.

Trust and invested effort also pay off in The Men Who Won’t Stop Marching, Alison’s 2008 account of band culture on the Shankill Road. This is a community that can be defensive and inward facing, but the film-maker gets many of her best insights from Jordan, an 11 year-old who seeks the approval of his father Jackie. The latter has paramilitary form and eventually he takes his son to the Maze prison, where he spent time for an undisclosed act. Jordan has a sweet nature and a passion for his instrument. His life resonates like Billy in the Ken Loach film Kes, with a snare drum instead of falconry.

Trust and invested effort also pay off in The Men Who Won’t Stop Marching, Alison’s 2008 account of band culture on the Shankill Road. This is a community that can be defensive and inward facing, but the film-maker gets many of her best insights from Jordan, an 11 year-old who seeks the approval of his father Jackie. The latter has paramilitary form and eventually he takes his son to the Maze prison, where he spent time for an undisclosed act. Jordan has a sweet nature and a passion for his instrument. His life resonates like Billy in the Ken Loach film Kes, with a snare drum instead of falconry.

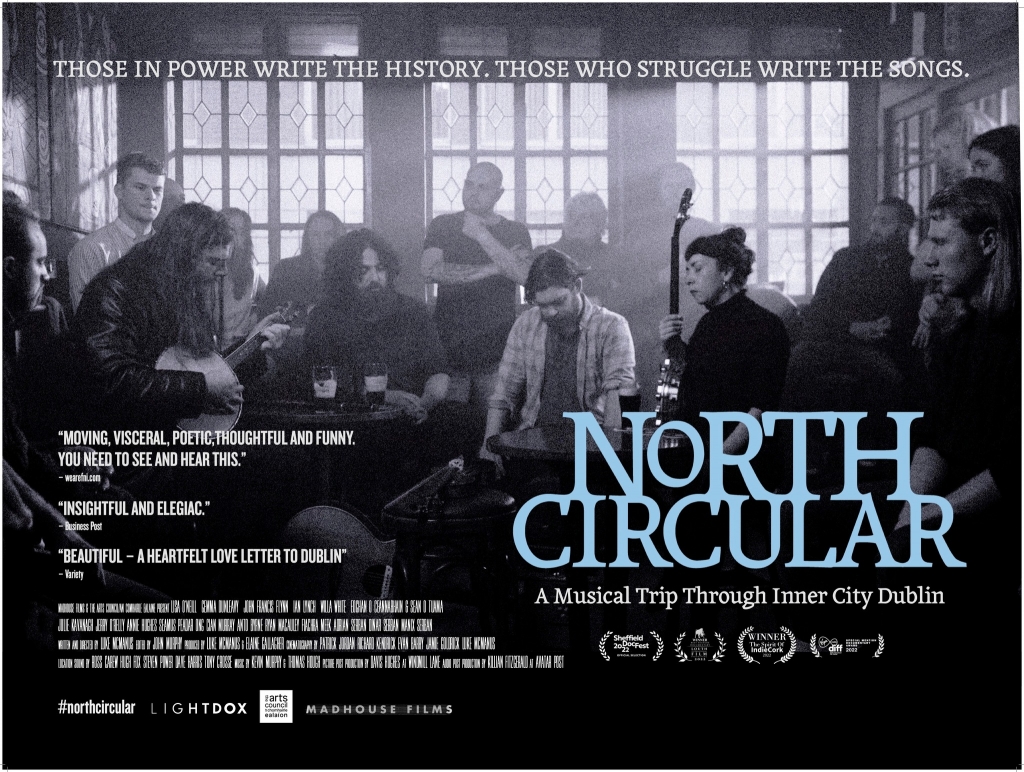

Docs Ireland has a vast programme and it’s barely possible to see the lot. Happily, there’s occasion to sit in the Beanbag Theatre and watch North Circular, a promenade from Dublin’s Phoenix Park to the port. Artists and vulnerable souls are squirreled away in the available spaces, alert to the brute economics that wants them gone. It is elegiac and uplifting. John Francis Flynn and regulars from the Cobblestone Pub sing up and stall the bulldozers. Gemma Dunleavy takes us to the actual heart of ‘Up De Flats’. The new art joins the tradition and the ancient tunes provide instruction. The song retains the strain.

Docs Ireland has a vast programme and it’s barely possible to see the lot. Happily, there’s occasion to sit in the Beanbag Theatre and watch North Circular, a promenade from Dublin’s Phoenix Park to the port. Artists and vulnerable souls are squirreled away in the available spaces, alert to the brute economics that wants them gone. It is elegiac and uplifting. John Francis Flynn and regulars from the Cobblestone Pub sing up and stall the bulldozers. Gemma Dunleavy takes us to the actual heart of ‘Up De Flats’. The new art joins the tradition and the ancient tunes provide instruction. The song retains the strain.

Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter