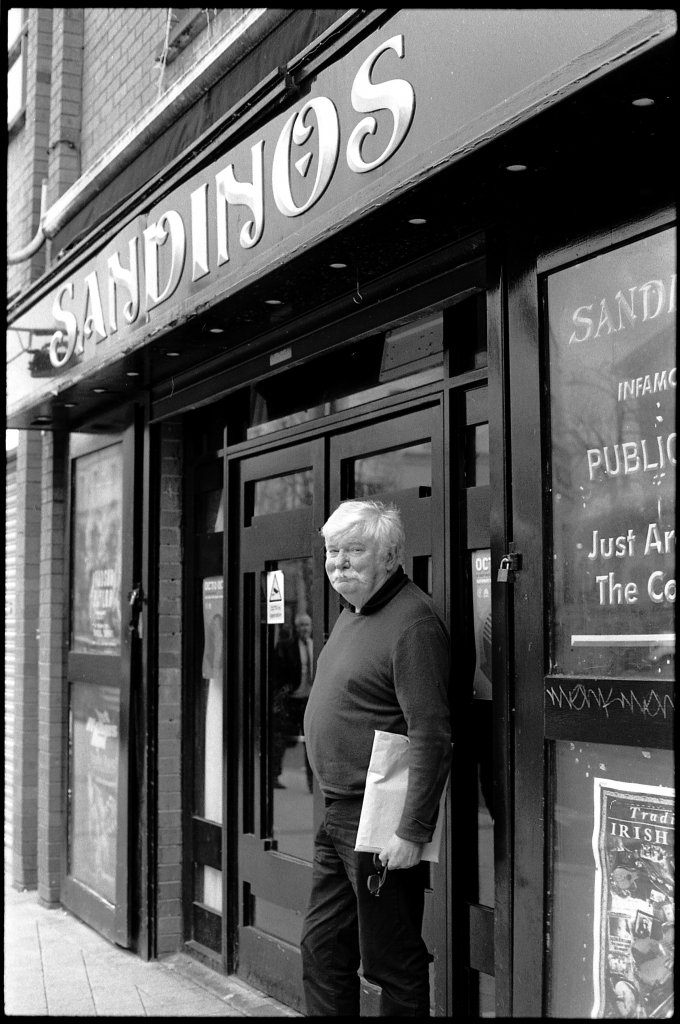

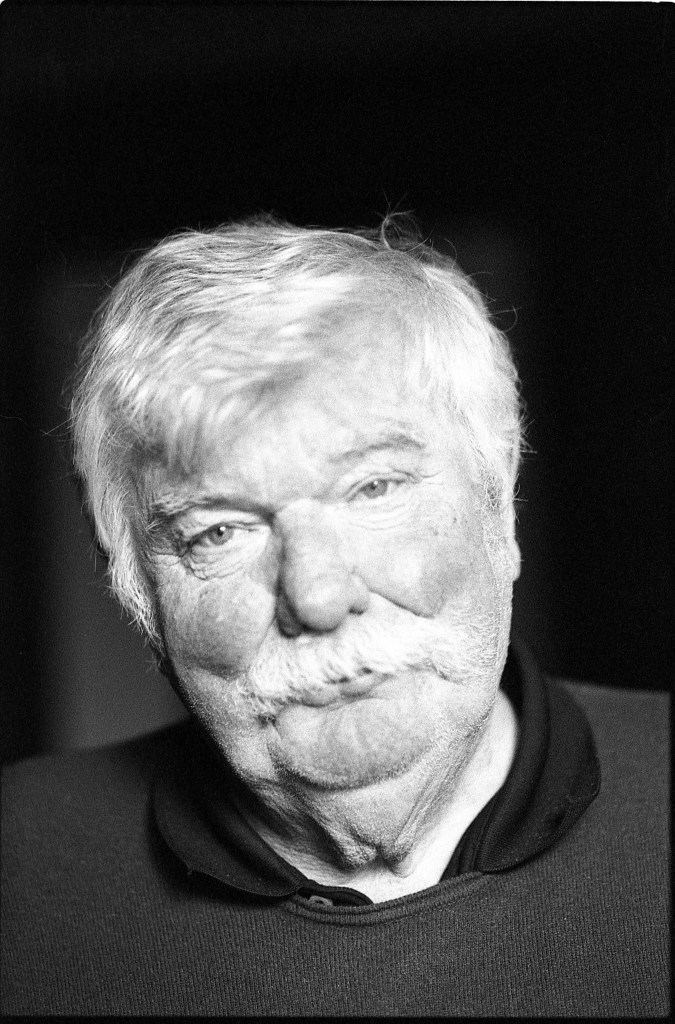

Joe Mulheron, raised in Belfast, performed with The Men of No Property in the 70s, singing about resistance and civil rights. He was inspired by radical folksingers like Woody Guthrie. He worked with Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger and some of his repertoire found its way into the Christy Moore songbook. He later relocated to Derry and opened up Sandinos in 1997, a music bar and a gathering place where left-wing movements were celebrated and furthered.

Joe Mulheron, raised in Belfast, performed with The Men of No Property in the 70s, singing about resistance and civil rights. He was inspired by radical folksingers like Woody Guthrie. He worked with Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger and some of his repertoire found its way into the Christy Moore songbook. He later relocated to Derry and opened up Sandinos in 1997, a music bar and a gathering place where left-wing movements were celebrated and furthered.

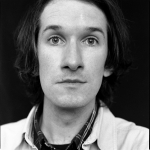

Joe Mulheron, March 20, 2019. Photo © Stuart Bailie

Joe passed away on May 9, 2023, aged 76. His legacy has been celebrated by many musicians including Lankum. “His company and singing will be sorely missed,” they stated, “but the many songs he wrote will live on. Rest in power.” These thoughts were seconded by Eamonn McCann in Derry in a quote to Belfast Live. “Joe was a great patron of the arts… he had a great talent for writing songs very quickly about particular events.”

Terri Hooley published one of Joe’s first songs, ‘The Leaving Of Belfast’, in his underground magazine Id. They socialised in Terri’s folk club on High Street and at Joe’s flat in Duncairn, north Belfast. “Can’t believe Joe is gone,” Terri said. “Our friendship lasted nearly 60 years. He will be missed.”

Charlotte Dryden

Charlotte Dryden, CEO of the Oh Yeah Music Centre, remembers the importance of Sandinos when she was starting to put on events in her hometown. “His legacy extends long before I met him but I met Joe when I was putting on gigs around Derry. He liked what I was trying to do and offered me a chance to run a night in Sandinos which I was delighted about. He was very supportive of the musicians, the live scene, the poets, revolutionaries and alternative thinkers of the city. Sandinos was a safe space and I’ll always have fond memories of our chats when I was there. So sad to hear of his passing.”

He was writing songs as a teenager and performing with an east Belfast friend, Dave Scott and his wife Maureen O’Hare. They performed at the original Sunflower Folk Club and connected with Brian Moore from Ardoyne. It was Moore and Mulheron who became the mainstays of the act that eventually emerged as The Men of No Property, named after a Wolfe Tone quote.

“It was a protest group,” Joe told me in 2017, as I was researching my Trouble Songs book. “We weren’t your average rebel band in that sense. Our songs came out of the Civil Rights and People’s Democracy and that sort of stuff. We were singing mainly in the shebeens back in ’69 and ’70. The different ghettoes opened up their own sort of social clubs, for want of a better word. We tended to play up and down the Falls Road, in the Ardoyne and the New Lodge Road. We were constantly on Radio Free Belfast. It was based in The Long Bar in Leeson Street and it was up in the first floor lounge and we broadcast live every night and half of Belfast sat up through the night tuned in, not even because of the music.”

They toured England, supported by the Troops Out movement. Around 1969 they performed at the London club, The Critics Group, where Ewan MacColl held sway and often issued barbed advice. Joe wasn’t over-awed. “MacColl was a dry boy. He said, ‘Mulheron’s introductions lasted longer than some of the songs’. I said, ‘That’s ’cause youse know fuck all over here – we have to explain ourselves’.”

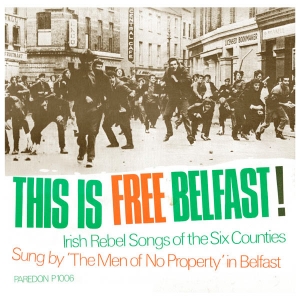

The American folksinger Barbara Dane financed their records and released them on her Paredon records imprint, which she managed with Irwin Silber, former editor of Sing Out! magazine. Their label specialised in international revolutionary music. “She was very left wing, to say the least,” Joe remembered.

The American folksinger Barbara Dane financed their records and released them on her Paredon records imprint, which she managed with Irwin Silber, former editor of Sing Out! magazine. Their label specialised in international revolutionary music. “She was very left wing, to say the least,” Joe remembered.

Bernadette Devlin wrote their sleeve notes. Their 1971 debut album, This Is Free Belfast! Rebel Songs of the Six Counties, included ‘The Bogside Man’, a startling re-write of the old sea shanty, ‘Hog Eye Man’, which they had learnt from the McPeake family.

“Steady on your aim with the petrol bomb,

Don’t throw it son, ’til the peelers come,

I am the Bogside man.”

There were no names or credits on the records. There were no contact details. Neither were the albums sold in regular record shops.

“You might have thought differently by listening to the likes of ‘The Bogside Man’ but we tried to keep the sectarian thing out of the mix,” he said. “What we also found was that we’d be singing these deep, political songs and half the time the working-class people in the ghettoes would be clapping away and not really listening to the words. I ended up consciously having to write some of the songs where there was a twist or a funny bit at the end. Just to get the people’s attention.”

Joe Mulheron, March 20, 2019. Photo © Stuart Bailie

While Joe and his colleagues were adding wit to their repertoire, other writers were coming up with stirring, sentimental songs like ‘The Broad, Black Brimmer’. Attributed to Art McMillan, this song evoked the paramilitary uniform of the original IRA, bequeathed from the late father to the son – the brimmer being the headgear worn during the 1919-21 Irish War of Independence. Later, Joe would respond with a piece of satire, writing a Palestine Liberation Organisation anthem in an Irish rebel style – ‘The Wee White Turban’.

“It was a tongue-in-cheek, a take-off. It’s very difficult to explain. We were pissed off with ‘The Broad, Black Brimmer’ because every drunk in every pub in Belfast was singing it, whether they could sing or not. So, I wrote that song as a spoof. But I tried to put a bit of politics into it – I didn’t want people to think I was sending up the PLO. I was really sending up the republicans. You’re gonna have to take your oil, as they say in Derry. Take a bit of criticism.”

Joe was bashful when he was reminded of another song, ‘The Lid of My Granny’s Bin’, which was recorded by Blackthorn and then appeared on Christy Moore’s album, The Spirit of Freedom. “It was a funny little bit of a song back in the days when the women in the ghettos went out and rattled the bins when the soldiers were coming in.”

Joe was bashful when he was reminded of another song, ‘The Lid of My Granny’s Bin’, which was recorded by Blackthorn and then appeared on Christy Moore’s album, The Spirit of Freedom. “It was a funny little bit of a song back in the days when the women in the ghettos went out and rattled the bins when the soldiers were coming in.”

It was the Men of No Property who passed on to Christy a momentous song by the New York writer Jack Warshaw, ‘No Time For Love’. He then recorded it with Moving Hearts and it became one of Christy’s signature live songs, but it dated back to the Ewan MacColl days at the Critics Group, originally titled, ‘If They Come in the Morning’.

The cover of the first album showed a riot on William Street, Derry. The image had been chosen by Barbara Dane and The Men of No Property were ribbed by their Belfast friends when they saw it. Still, Joe was happy to relocate to the north-west and to set up his bar on Water Street. “I’m a Belfast man and I love Derry and I can say that. I can praise the city not being from here and the first thing I discovered when I came to Derry was the music and so many people could sing and had learned songs, far, far more than I really picked up in Belfast or in Dublin or anywhere else. I came to Derry, everybody could sing and they were good singers and they enjoyed it. They wrote songs as well about the local conditions and things that happened here.”

Paul Connolly

The affection was reciprocated by local musicians like Paul Connolly from the Wood Burning Savages, who wrote this about Joe: “An ardent music lover, tirelessly community minded and always with a focus on welcoming everyone through the door and making them feel like they were at home. Thoughts with his family and all at Sandinos.”

A few years ago, I talked with Joe about the power of the song. He responded warmly. “It was always that political message to get the news out to the ordinary people of the north about what was really happening. I’m not saying we succeeded, but I think we contributed and I think that that is a tradition that’s been going on for generation after generation.

“That’s why people still sing songs of 1798 and they still sing songs about 1916. Nobody remembers a newspaper or maybe you’ve read a book, but people remember the songs.”

May the songs always be sung.

Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter