If you were exiled and homesick in the Eighties – part of that wash of Irish émigrés from a damaged island – then you may have taken recourse in a Paul Brady album, Hard Station. Alongside Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, it was a point of focus and a reassurance. We brought the record out when the drink was in and the self-possession was due for a crash.

If you were exiled and homesick in the Eighties – part of that wash of Irish émigrés from a damaged island – then you may have taken recourse in a Paul Brady album, Hard Station. Alongside Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, it was a point of focus and a reassurance. We brought the record out when the drink was in and the self-possession was due for a crash.

Paul Brady made the listener understand that you were hardly the first one off the boat but still, the culture shock was understandable and the loneliness was a rite. The key song off the record was ‘Nothing but the Same Old Story’, a ragged account of Paddy in the Smoke, working the bars and missing someone in the hometown. Back then, every Irish accent was suspect, the voice of a seeming perpetrator in the conflict. Brady acted it all out and registered the bigotry. “We’re nothing but a bunch of murderers,” he sang, furious with the typecasting.

Also, the record wished to break with that immigrant tradition, to reach the safe place. And that’s the dynamic of the song ‘Crazy Dreams’, a vow to pack the case and exit the scheme. Brady’s voice is so ragged and convincing. Several times, he returned to the mastertapes and tweaked the mixes of Hard Station but the soul of it was always more precious than the keyboard settings.

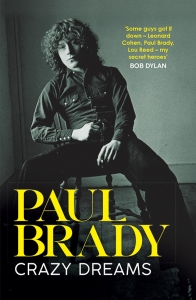

Crazy Dreams is now the title of a hugely readable life story. Paul Brady was essentially the guy in the lyric. His first commercial run at success with the folksy tones of The Johnstons had left him stranded and distressed in Long Island. There was a transatlantic affair (with his future wife) and various music industry defeats. It was a difficult turnaround before he could sit in with Planxty and Andy Irvine and bring a remarkable sense of drama to the old ballad, ‘Arthur McBride’.

Crazy Dreams is now the title of a hugely readable life story. Paul Brady was essentially the guy in the lyric. His first commercial run at success with the folksy tones of The Johnstons had left him stranded and distressed in Long Island. There was a transatlantic affair (with his future wife) and various music industry defeats. It was a difficult turnaround before he could sit in with Planxty and Andy Irvine and bring a remarkable sense of drama to the old ballad, ‘Arthur McBride’.

The book is open about Brady’s anxieties, his periodic career swerves and the family strains that were priced into the touring life. You also come away with a better understanding of the contrary energies in his music story. The received wisdom was that he had betrayed the folk scene to coin it as a rocker, but the actual trail has a lot more nuance and random connections.

He writes very well about a childhood in Strabane – a town chosen by his teacher parents so they could work on alternate sides of the border. He was gifted the notion of cultural tolerance and a disregard for fixity. Interestingly, he says that Irish traditional music was not a priority for the nation in the 50s. He invested his summers in the Donegal Gaeltacht but his UCD life was more about Chuck Berry, Ray Charles and John Mayall.

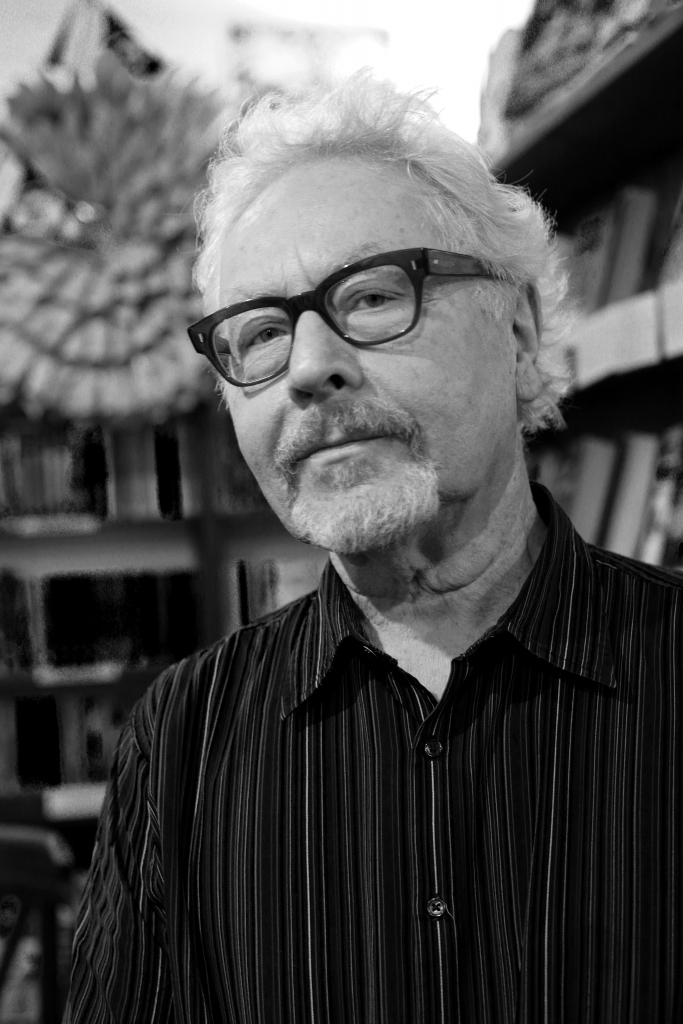

Paul Brady, No Alibis Bookshop, Belfast. By Stuart Bailie

Paul remembers Bundoran with unfiltered affection. Later, he escorts the reader through the music bars of Dublin, to soirées at O’Donaghoe’s and Slattery’s. He was convivial with Phil Lynott, Rory Gallagher and there were encounters with magisterial figures like Willie Clancy and Séamus Ennis. He meets David Bowie at the Albert Hall in 1970 and there’s a conversation backstage about twelve-string guitars. ‘Space Oddity’ was in David’s set and the engines were on.

None of this feels boastful. Later, he gets testy with Bono and regrets it. A couple of his songs have been adopted by Tina Turner and there’s a messy scene when he joins her onstage to sing ‘Steel Claw’. He paints himself up as being slightly gauche and subsequently he gets stoned and paranoid.

Eric Clapton treats him well on tour and so does Mark Knopfler. And amazingly, Bob Dylan wants him to demonstrate the fingerings for ‘The Lakes of Pontchartrain’. Brady is respectful of the moment and rather graciously does not complain in public when Dylan borrows his arrangement of ‘Arthur McBride’ with a larcenous ‘Trad. Arr’ credit.

The writing of ‘The Island’ is a captivating story. Paul had kept the tune with him for some time. He rightfully agonised over the tone and the content of a lyric about the conflict. Many will agree that it’s his outstanding work, a repudiation of violence when many of his Irish peers were sympathetic – or at least ambivalent – about an armed struggle.

The writing of ‘The Island’ is a captivating story. Paul had kept the tune with him for some time. He rightfully agonised over the tone and the content of a lyric about the conflict. Many will agree that it’s his outstanding work, a repudiation of violence when many of his Irish peers were sympathetic – or at least ambivalent – about an armed struggle.

He remembers finishing the song as an unconscious act. It had turned into a slow tango – a homage to his father’s old repertoire. He improvised some of the words and arrived at an ironic position:

“These young boys dying in the ditches is just what being free is all about…”

The song had a pivot and so it could be resolved. It took a few loose moments at the microphone to find it, but also a lifetime of craft and character-building to let him to carry it thus.

Stuart Bailie

(Review extracted from Issue 9 of Dig With It magazine, out November 7)

Twitter

Twitter