We meet in a park on the south side of Dublin Bay. The clouds are up and we talk loosely about band rehearsals, bicycle maintenance and the joy that a teenage Conor J. O’Brien once found in a new Radiohead release, saving up his first listen of Kid A for the morning before school.

We meet in a park on the south side of Dublin Bay. The clouds are up and we talk loosely about band rehearsals, bicycle maintenance and the joy that a teenage Conor J. O’Brien once found in a new Radiohead release, saving up his first listen of Kid A for the morning before school.

He chats about life drawing classes in Berlin, which he follows online, organised by Dave Hedderman, his old bandmate from the days of The Immediate. Conor’s drawings, at least the ones he shares with us, are vivid and peculiar, something we might discuss later. But like his music, they suggest turbulence versus order, some reassuring details in the face of the unknown.

We had previously spoken on the phone, but the changing patterns of pandemic life suggested that we might meet at a respectful distance, take a few photographs and learn more about the ever-stimulating world of Villagers. These are bonus moments in another messy year and we find the worth in them.

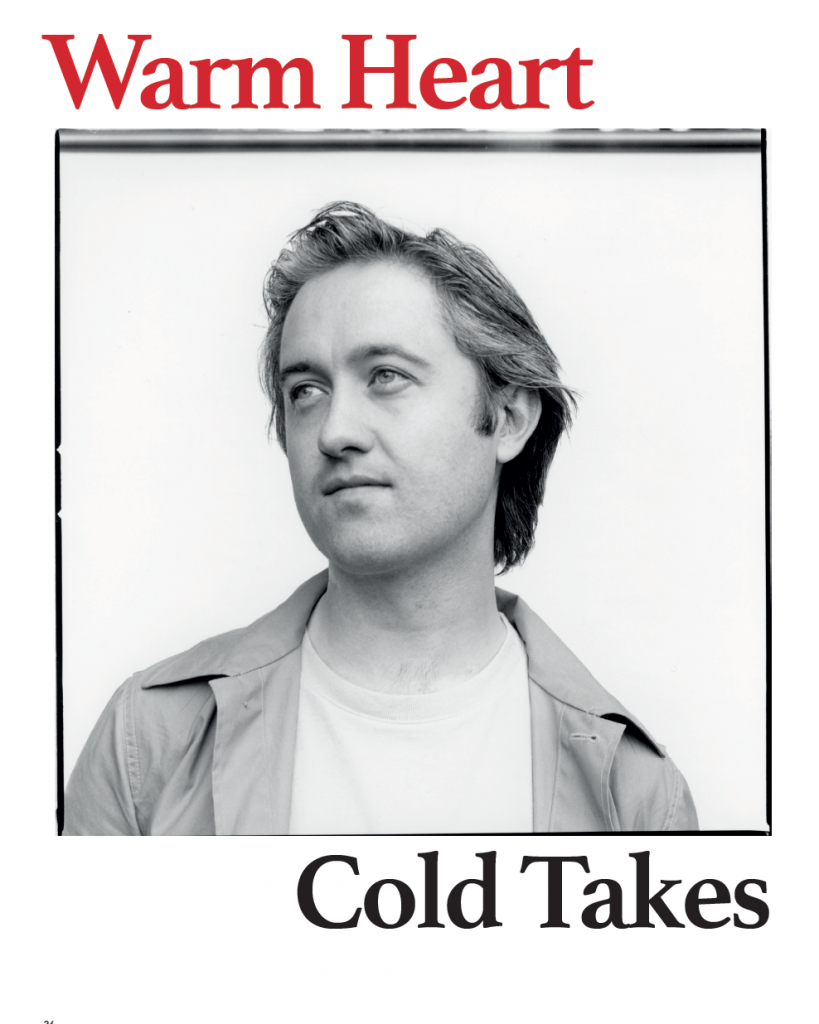

Conor photography by Stuart Bailie

Conor is generous with his ideas and his time. He has an expressive face and an intellect that does not settle for the humdrum. He talks about the politics of Bernadette Devlin and he’s been watching old, incisive footage of the American debater, William F. Buckley Jr. Even in a fairly relaxed setting it seems that Conor is determined not to fall into the hostile trenches of online opinion.

He talks about the problems of the “hot take” and a culture that favours noise and grandstanding. That’s not the Villagers way, and you sense that he’s encountered pain from such a source. Rather, he favours inner reflection and the “cold take” that a searching mind can try for. So, much of our two conversations is taken up with this.

“As I get older,” he says, “music for me becomes more and more a place to go where you an explore nuance and you see things in more interesting ways than they’ve been explored on everyone’s screens and on the internet.

“I think when I was younger, I used to have this kind of idea that I needed to show people my pain and that my pain was really unique and show them how deep I got with these critical thoughts in my mind about how the world is run and all this kind of stuff. And then you actually go through crazy shit in your life, really dark stuff, and you realise how music is where you should go to for the warmth and the escape and the realisation that we are all in this shitshow together. I think this is a culmination of that. On the last record I was starting to move there and this one is probably the must celebratory tone I’ve so far mustered.”

This was an aim of the first Villagers release of the year, ‘The First Day’. It was written after a festival, Another Love Story at Killyon Manor in Meath. Conor wrote the song in 2019 to keep the party rolling in his soul. Back then it was an electronic tune called ‘Love Story’, but by the time he’d brought it to the band in 2020, it was making other assertions. Their final session ended on the announcement of lockdown and fortunately, work on various songs was on multi-track. And so Conor had the material in his home studio to finish the album. Those words must have been an incentive to move on, surely?

This was an aim of the first Villagers release of the year, ‘The First Day’. It was written after a festival, Another Love Story at Killyon Manor in Meath. Conor wrote the song in 2019 to keep the party rolling in his soul. Back then it was an electronic tune called ‘Love Story’, but by the time he’d brought it to the band in 2020, it was making other assertions. Their final session ended on the announcement of lockdown and fortunately, work on various songs was on multi-track. And so Conor had the material in his home studio to finish the album. Those words must have been an incentive to move on, surely?

“It emboldened me to emphasise the more idealistic and positive vibes as much as possible. To bring it somewhere more escapist, I guess.”

Human connection, right?

“Yeah. In all of its forms. A sense of that transcendental joy in human connection. Still holding onto that and remembering how we are all kind of the same, really, when it comes down to it. And trying not to listen too much to all these the way the internet is, trying to label us and make us different.

“Starting to decide to get right into working on the record and everything we had done together as a band and filling my days with that – it kind of kept me sane. And it really helped me maintain a focus on something. When you’re making an album, it’s a good way of feeling like there is some sort of linear motion in your life.”

He took long walks in the night of Dublin. Like many people, he was aware of the empty streets and the pervasive quiet. Normally the streets around Camden Row would have been relentless but now he could easily record his piano playing on a song called ‘Full Faith In Providence’. As with some of the songs on his previous record, he was nakedly spiritual. But not religious…

“I don’t think religion is the problem,” he asserts. “I think it’s dogma. I think it’s when people use texts in order to try and maintain some sort of status quo, which is probably not helpful to one particular group in society. That’s the problem. Spirituality and all that stuff is quite often targeted by modern atheists or agnostics or whatever. But it’s not really that, for me. It’s the power that becomes engulfed in it and which stems from it. They’re the problems.

“In The Art of Pretending to Swim, the lyrics (of ‘Again’) were, “I found a place in my heart for God in the form of art”. It’s just claiming words for yourself and realising that it’s just another way of trying to discuss this unsayable thing. This idea that we are all extremely similar – without being too new agey, or hippy. That’s the function of art, you know? It’s just all these silly arguments and discussions which are constantly happening. It’s stepping outside of that sometimes, and perhaps trying to express something which words won’t fully express.”

“In The Art of Pretending to Swim, the lyrics (of ‘Again’) were, “I found a place in my heart for God in the form of art”. It’s just claiming words for yourself and realising that it’s just another way of trying to discuss this unsayable thing. This idea that we are all extremely similar – without being too new agey, or hippy. That’s the function of art, you know? It’s just all these silly arguments and discussions which are constantly happening. It’s stepping outside of that sometimes, and perhaps trying to express something which words won’t fully express.”

Would regard yourself as a quester? Is that a fair assumption?

“Yeah. I dunno. I try and write good music. Things come into my mind and they so seem to have… I seem to return to certain themes and I don’t really know why.”

Do the new songs bully you into existence or do they charm you? How do they announce themselves?

“Lots of different ways. They are usually reworked quite often. A couple of them were brought really unfinished. One of them is just a jam, called ‘Restless Endeavour’. They were chords I had played on piano for the last ten years really and I had tried to write lyrics, but it just stayed in my notebook or in my voice memos.

“One day we were with the band and we just jammed that and the next time I came back with a slightly more finished thing. We basically spent a couple of hours jamming it out and I was talking to the guys with their headphones saying ‘slow down’, ‘speed up’, or the mood we should have. And that 15 minute recording was edited at home. You’re basically just hearing the very end of the jam. With Ross (drummer Ross Turner), his energy is just peaking he’s been jamming the last ten mins, speeding up. So we decided to bring it in when the energy was peaking. You’re only hearing the last three minutes.”

I really like ‘So Simpatico’. It’s so sensual and I love the talking part and a sax playing. It’s like an old Marvin Gaye tune.

“I keep getting told it’s a bit Dexys, as well. People reference them too.”

Well, I’m getting Marvin.

“I’d go with that a bit more, to be honest. Thanks, that was about to go in the bin. All the verses had so many words in them and I was just really over-complicating it. I couldn’t figure out. Ross made me play it for him one day and he just said, we have to record that regardless, So we recorded it, with too many words and with too many ideas. And then came back the next time realising that, oh God, if you just sing, it actually doesn’t need all these words. It doesn’t need to complicate itself, it needs to open up. I think half the trick of writing is editing.”

In the song ‘Circles in the Firing Line’ there’s a lyric about “the United States, demagogic logic”. When I heard that, I was thinking of dark forces in high office.

“Definitely. There are some other lines. There’s a song called ‘Momentarily’ on the record. The lyrics now are, “it’s a forest fire on the front page and how we’re all gonna pay”. originally the lyrics were, “the fascist fuck in the White House”. But Danny, bass player, said, you know you might be talking about Bernie Sanders this time next year? I thought, ok, maybe change that line. But also, it’s too on the nose. I think sometimes the power in words and music can be better if you leave a lot more to the imagination.

“But ‘Circles in the Firing Line’ was definitely just like you said, constantly reading the news everyday or looking at the news on TV. Like, what is happening? The thing about someone like – don’t even want to say his name – being at the highest level, one of the most powerful men on Earth, it has a knock-on effect. For the ability of people to think critically and even people who might be on the opposite side of opinions about topics.

“I think a lot of people lowered their expectations or critical capacities over the last four or five years and it has the butterfly effect. We are slightly recovering from that collective, post-traumatic stress thing. Also with that song, I was reading about this idea of the ‘negative capability’ which Keats used to talk about. He enjoyed the idea of being able to keep two completely opposing thoughts in his mind whilst not abandoning reason.

“That’s where arts and creativity and I guess science and development in lots of different areas comes from. I feel like everybody’s living on their screens right now and corporations are controlling the way people think. In an Orwellian sense, it’s starting to really eat into culture and that song was just tapping on that a little bit. But also a reason to get an electric guitar and you know… shred.”

In August 2019, Villagers played a festival date on the island of Vlieland in the Netherlands. Afterwards, they went night swimming in the North Sea, enjoying the breeze. Conor had been talking to Brendan Jenkinson, the band’s keyboard player about his interest in these scientific and perhaps even the mystical significances in the numeral. And then Brendan pointed up to the firmament. There it was. An awesome constellation, the Great Bear.

In August 2019, Villagers played a festival date on the island of Vlieland in the Netherlands. Afterwards, they went night swimming in the North Sea, enjoying the breeze. Conor had been talking to Brendan Jenkinson, the band’s keyboard player about his interest in these scientific and perhaps even the mystical significances in the numeral. And then Brendan pointed up to the firmament. There it was. An awesome constellation, the Great Bear.

“We saw Ursa Major in the sky. We saw the seven stars, as the main asterism from Ursa Major. And that spawned the beginning of ‘Song In Seven’ because I was like ‘this number seven is not going to go away’ so we did it in 7/8. That’s one of my favourites.”

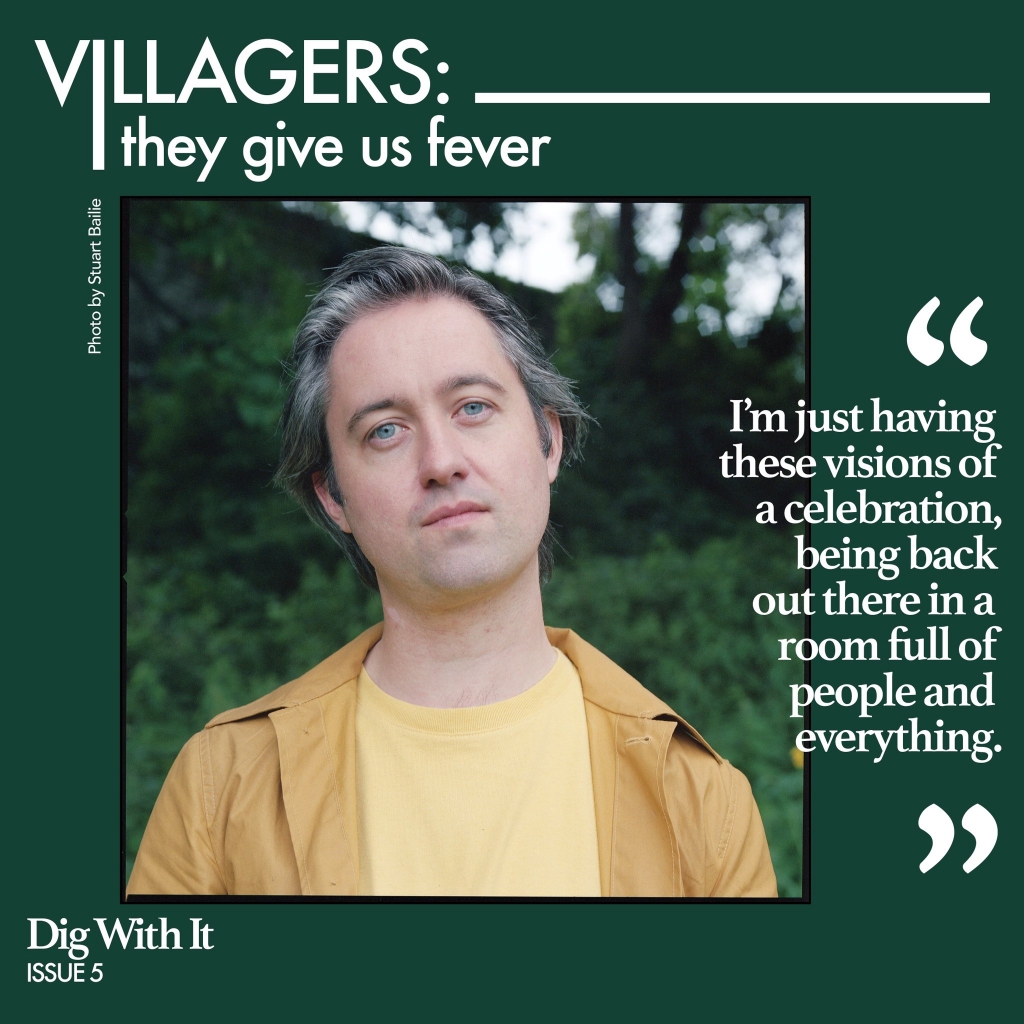

Happily, Villagers play The Empire in Belfast on November 7. We’ll say that it augurs well. Does Conor have a picture in his head of what these autumn shows will look like and how it might work emotionally?

“I just got some recordings back yesterday from the rehearsals and it was already sounding kinda trippy and cool. Some of the songs were already going to a new place a little bit. If they’re already beginning to do that now, I’m wondering what they’ll be like when they get to the stage.

“I’m just having these visions of a celebration, being back out there in a room full of people and everything. Really feeling it and actually having a renewed love for it. A renewed sense of, ‘Oh God, I got a taste of when we can’t actually do this’. I think that will all be happening on the night.”

So much significance. A heap of expectation. And also the chance for musicians and their people to earn their worth. Conor J. O’Brien is smiling and getting his hustle on. As you might.

“So, bring seven friends to the show. Buy seven tickets each.”

Stuart Bailie

(This is extracted from a longer interview, the cover story of Dig With It, Issue 5. You can buy the magazine and take out a subscription here.)

The Villagers album, Fever Dreams, is out now.

Twitter

Twitter