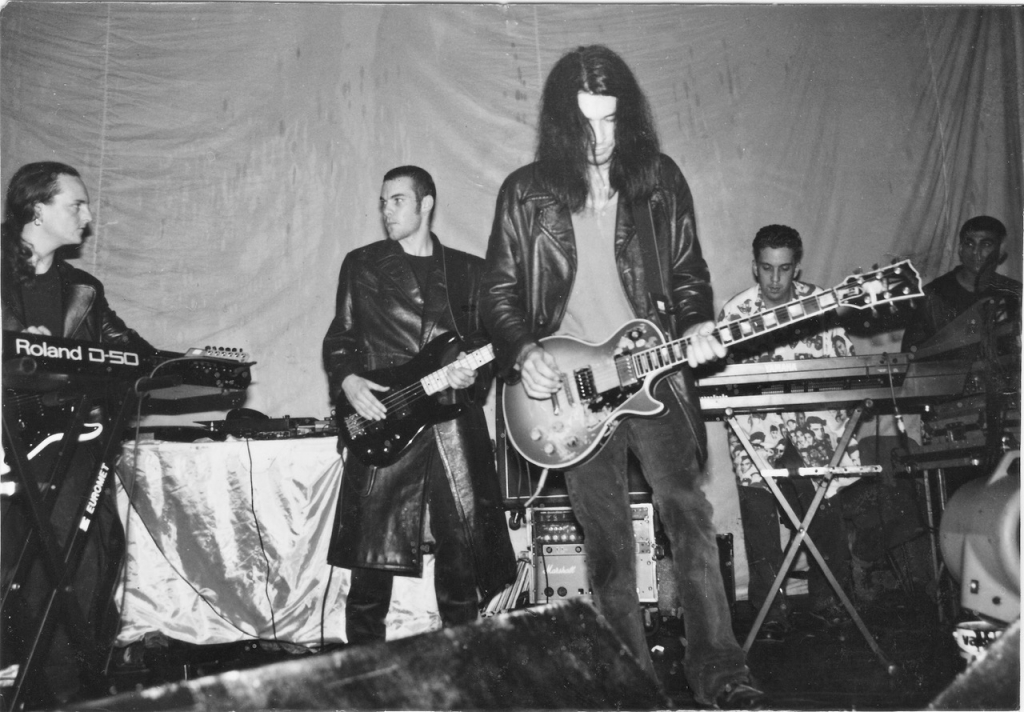

We’re watching Sabres of Paradise at Sugar Sweet in Belfast, September 25 1993. The dress code is leather trench coats for Jagz, Gary, Phil and Nick plus an Elvis shirt for Andrew Weatherall, freshly liberated from the racks of American Madness. The message is large, swaggering beats, spirit of Suicide plus elemental, rock and roll lurch. “I’ve always liked groups that look like a horrible gang,” says Andrew with the conspiratorial laugh. “Now I’ve got one of my own.”

We’re watching Sabres of Paradise at Sugar Sweet in Belfast, September 25 1993. The dress code is leather trench coats for Jagz, Gary, Phil and Nick plus an Elvis shirt for Andrew Weatherall, freshly liberated from the racks of American Madness. The message is large, swaggering beats, spirit of Suicide plus elemental, rock and roll lurch. “I’ve always liked groups that look like a horrible gang,” says Andrew with the conspiratorial laugh. “Now I’ve got one of my own.”

They motion out of the haze to ‘Theme’ and ‘Smokebelch II’. The Conor Hall has been customised to the Sugar Sweet purpose by David Holmes and Iain McCready, receptive to the Sabres set and the DJ tunes. It’s the first time that most of us have heard a club play of ‘Open Up’ by Leftfield and Lydon, another punk rock derivative that excites the evening set. Ashley Beedle has flown over for the fun and the Acid Jazz guy whose name escapes me is onstage blowing a bugle. At the end, David Holmes plays his towering remix of ‘Smokebelch II’ and even the security guys are losing it.

They motion out of the haze to ‘Theme’ and ‘Smokebelch II’. The Conor Hall has been customised to the Sugar Sweet purpose by David Holmes and Iain McCready, receptive to the Sabres set and the DJ tunes. It’s the first time that most of us have heard a club play of ‘Open Up’ by Leftfield and Lydon, another punk rock derivative that excites the evening set. Ashley Beedle has flown over for the fun and the Acid Jazz guy whose name escapes me is onstage blowing a bugle. At the end, David Holmes plays his towering remix of ‘Smokebelch II’ and even the security guys are losing it.

I’m in the company of Jeff Barrett, co-founder of Heavenly Records, who also does PR for acts like Happy Mondays, Primal Scream and now the Sabres. Jeff and Andrew have form – the Weatherall mixes and remixes of Sly and Lovechild, St. Etienne and Flowered Up were audacious moments in the Heavenly catalogue. Later, Andrew will do tremendous work with Beth Orton and others. These sympatico mates were early adopters of acid house and are still alert to new ideas. Weatherall and Barrett know their tunes and relate to dub, soul and sedition yet are not weighted by the past. And so this contrary energy continues afterwards at Star hairdressers in Belfast with a carry-out disco and the trenchcoat mafia, misbehaving. At one point Jeff pulls a cassette out of his jacket and plays ‘Born To Run’ on the tape deck. He has just married Wendy and so the tune has significance. He relates to the words and everybody is roaring him on.

Since Andrew’s unexpected death on February 17, many people have been fetching up their own Weatherall stories. Most of them recall the kindness, the tunes and the classic one-liners. Andrew was a fan of Peter Cook and he got some of his deadpan manners from the comic. He was also a fan of Cook’s life ethic – do the work when it suits, be wary of ‘the career’ and enjoy the longueurs. Screamadelica was Andrew’s greatest early achievement and he turned down lots of requests to make lesser bands sound so benighted. So, the Sabres of Paradise were offered huge deals but settled for an album release on Warp Records. Soon after, they were history, willfully terminated. Weatherall continued as a boss curator and a DJ with a penchant for rockabilly, brute abstraction (he was only half-joking about the mythical Panel Beaters from Prague) and sabotage of a brilliant stripe.

Since Andrew’s unexpected death on February 17, many people have been fetching up their own Weatherall stories. Most of them recall the kindness, the tunes and the classic one-liners. Andrew was a fan of Peter Cook and he got some of his deadpan manners from the comic. He was also a fan of Cook’s life ethic – do the work when it suits, be wary of ‘the career’ and enjoy the longueurs. Screamadelica was Andrew’s greatest early achievement and he turned down lots of requests to make lesser bands sound so benighted. So, the Sabres of Paradise were offered huge deals but settled for an album release on Warp Records. Soon after, they were history, willfully terminated. Weatherall continued as a boss curator and a DJ with a penchant for rockabilly, brute abstraction (he was only half-joking about the mythical Panel Beaters from Prague) and sabotage of a brilliant stripe.

Lots of Andrew’s verve and intelligence is refracted through this Jockey Slut tribute. It’s a beautiful magazine, fitting for an artist who was occupied in the early days with the Boy’s Own fanzine, the journal of Shoom and the pioneer ravers. Vintage features from Jockey Slut reveal an artist in transit, never tiresome, partial to tattoos and timbales. Old friends such as Richard Norris have written up fresh insights. Such an artist. Just as Joe Meek made futuristic productions in a cramped rental on the Holloway Road, so Weatherall did some of his best work above a tandoori house in West Hounslow. Later stories in this Jockey Slut special are borrowed from other fanzines and video interviews. Andrew continued to evolve, copping some of his later style from the Edwardian artist Augustus John, getting gnostic with the Cathars and the strange world of Arthur Machen. He was more of an aesthete, less of a superstar DJ. It will take decades to unravel Andrew’s substance (future scholars may fixate on One Dove, The Asphodells and those NTS treasure drops), but this compendium is a needful start.

Believe In Magic is an account of Heavenly Records, a parallel story with many of the same travellers. Jeff was raised in Nottingham and was employed in various record shops in Plymouth. He saw the worth in Alan McGee and Creation Records and by the early Nineties, Heavenly (Barrett in partnership with Martin Kelly) was a cause for delight, capers and uncommon pop. There was space on the schedules for two fierce Manic Street Preachers records, ‘Motown Junk’ and ‘You Love Us’. St. Etienne chanced it well and lesser-knowns like Fabulous were flamingly worthwhile. Jeff ran the Phil Kauffman Club at The Falcon in Camden, also home to The Rockingbirds, who loved Bobbie Gentry and played it lonesome. ‘Gradually Learning’ was another Heavenly favourite, a sign that there were no limits on the company style.

Believe In Magic is an account of Heavenly Records, a parallel story with many of the same travellers. Jeff was raised in Nottingham and was employed in various record shops in Plymouth. He saw the worth in Alan McGee and Creation Records and by the early Nineties, Heavenly (Barrett in partnership with Martin Kelly) was a cause for delight, capers and uncommon pop. There was space on the schedules for two fierce Manic Street Preachers records, ‘Motown Junk’ and ‘You Love Us’. St. Etienne chanced it well and lesser-knowns like Fabulous were flamingly worthwhile. Jeff ran the Phil Kauffman Club at The Falcon in Camden, also home to The Rockingbirds, who loved Bobbie Gentry and played it lonesome. ‘Gradually Learning’ was another Heavenly favourite, a sign that there were no limits on the company style.

Paul Cannell was the house artist for a time, making bold sleeves and a label design that was a psychotic twist on the classic Red Bird graphic. They released books by Kevin Pearce and Paolo Hewitt and manifested a belief that the music should be lived out, like a Colin MacInnes novel. And so their offices above Ronnie Scott’s on Frith Street were loud, enthused and not likely to shirk a good time. Mid-period Heavenly brought in Doves, the Magic Numbers, Vines and Ed Harcourt. Sunday nights were spent in the basement of the Albany on Portland Street, where the Heavenly Social introduced the Dust Brothers (later the Chemical Brothers) as the house DJs and the pub corners were occupied by Tricky, Paul Weller, Norman Cook and the Scream team. Such evenings were recreational and messy but new music styles were being incubated. Elsewhere in the week, Tash from the label was hosting Heavenly Acoustic nights at the Crown & Two Chairmen on Dean Street, where Beth Orton and Dr. Robert got to finesse their visions.

Robin Turner was a staff recruit who gave Belushi levels of zeal to the job. Believe In Magic is his work. It’s a lovely book, affectionately done, like an adventure annual. Photographers such as Steve Gullick also make it sing. It is better in many ways to the louder narrative of Creation Records. Beyond the rowdy behavior there was artist development, ‘ears’ and perspicacity. Best of all, Heavenly still asserts itself, 30 years down the line, with Working Men’s Club, Mark Lanegan, Unloved and such schemes. Still, the postscript hurts. Jeff remembers his recently departed friend Andrew. “We were just two guys doing our best to dodge the squares,” he says. All true. It absolutely was the best.

Stuart Bailie

John Burgess (ed.), Andrew Weatherall: A Jockey Slut Tribute (Disco Pogo)

Robin Turner, Believe In Magic: Heavenly Records, The First 30 Years (White Rabbit)

Twitter

Twitter