There was an Irish market for recordings about political opinion and national identity. Two enterprises handled the bulk of the demand: Outlet and Emerald. Neither of them showed an especially partisan hand. They pressed up records from male voice choirs, rebel balladeers, pipers, céilí outfits and Protestant marching bands. By the early 70s, there was an established network that took in record shops and independent retailers but also saw value in street traders and market stalls in Glasgow, Blackpool, Crossmaglen, wherever.

There was an Irish market for recordings about political opinion and national identity. Two enterprises handled the bulk of the demand: Outlet and Emerald. Neither of them showed an especially partisan hand. They pressed up records from male voice choirs, rebel balladeers, pipers, céilí outfits and Protestant marching bands. By the early 70s, there was an established network that took in record shops and independent retailers but also saw value in street traders and market stalls in Glasgow, Blackpool, Crossmaglen, wherever.

Outlet was fronted by Billy McBurney, whose parents Patrick and Bridget had founded the Premier Records shop in Smithfield Market, Belfast in 1926, There had been profitable sidelines in gramophone needles and sheet music. They sustained the business over many difficult eras and claimed with some pride that it was the oldest record store in Ireland. Nineteen-sixty-six had been a fervent time for recordings, 50 years on from the Easter Rising and the proclamation of the Irish Republic. Patriotic songs had been selling well and Billy found the words and the occasion to exact the best result.

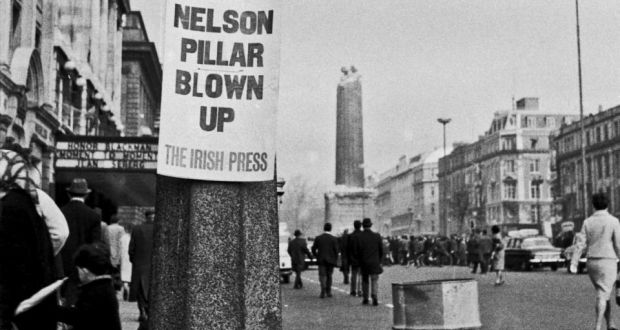

Dublin had rid itself of many symbols from the British Empire but there was still a statue of Lord Nelson on the main drag of O’Connell Street, on top of a granite column, 121 feet high. A splinter group of militants deposed the statue with explosives in the early hours of March 8 1966.

Dublin had rid itself of many symbols from the British Empire but there was still a statue of Lord Nelson on the main drag of O’Connell Street, on top of a granite column, 121 feet high. A splinter group of militants deposed the statue with explosives in the early hours of March 8 1966.

Billy wrote a lyric to commemorate the event, called ‘Up Went Nelson’. It was matched to the melody of the American Civil War anthem, ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’. A band of Belfast schoolteachers from St Thomas’s Secondary Intermediate on the Whiterock Road recorded it as the Go Lucky Four. Stomping and gleeful, it topped the Irish charts for eight weeks.

Billy wrote a lyric to commemorate the event, called ‘Up Went Nelson’. It was matched to the melody of the American Civil War anthem, ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’. A band of Belfast schoolteachers from St Thomas’s Secondary Intermediate on the Whiterock Road recorded it as the Go Lucky Four. Stomping and gleeful, it topped the Irish charts for eight weeks.

Other artists followed – Tommy Makem wrote ‘Lord Nelson’ and the Dubliners had their say with ‘Nelson’s Farewell’, but Belfast had trumped the major names.

Stuart Bailie

Extracted from Trouble Songs: Music and Conflict in Northern Ireland by Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter