When he was a boy, Lyndon Stephens sat in the back of the family Ford Cortina, loving the tunes on the 8-Track cartridge player. On the summer drives from Glengormley to Portrush, he listened to Glen Campbell and The Carpenters. Also, he was taken by the Paul Simon song about a boxer and a destitute kid, lost and defeated on Seventh Avenue.

When he was a boy, Lyndon Stephens sat in the back of the family Ford Cortina, loving the tunes on the 8-Track cartridge player. On the summer drives from Glengormley to Portrush, he listened to Glen Campbell and The Carpenters. Also, he was taken by the Paul Simon song about a boxer and a destitute kid, lost and defeated on Seventh Avenue.

Kris Kristofferson was on the playlist, singing ‘Me And Bobby McGee’ as the car headed north-west in the rain. And there was Charlie Pride, singing his famous song about the poor boy who had lost his girl to the bright lights and the social whirl. Against the odds, Charlie wonders if she might return when the shine wears off from her crystal chandeliers.

“These songs would blow your mind,” Lyndon says. “Even at such an early age there was so much information coming into your head. I suppose that’s the point where I really fell in love with music. It was like, wow – this can take me to another place, another country, to tell me about other people’s lives and how they feel. There’s a lot of that can be traced through to everything I’ve done, in terms of the record label. You’re really falling in love with the songwriter.”

Lyndon’s record label is called Quiet Arch. Based in the Oh Yeah Music Centre in Belfast, it has given shelter and succor to many outstanding songwriters. In the past four years, three of the winning albums in the Northern Ireland Music Prize have been Lyndon releases: Ciaran Lavery and Let Bad In (2016), Joshua Burnside and Ephrata (2017) and this year’s unanimous result, Borders by Ryan Vail and Elma Orkestra. Additionally, the Contender award for best new act in 2019 was another of his charges, Cherym from Derry.

“This has been the most prolific year we’ve ever had,” he figures. “We dropped four albums all at once. I don’t know if it was an experience we would want to repeat. But sure, it was fun to give it a go: Pat Dam Smyth, Beauty Sleep, Borders and Josh’s live album. I’m very proud of the artists. They all deserved it in their own way. Couldn’t be happier, really. And for Cherym to win the Contender Award – there’s massive potential with those girls. They’re are so funny and feisty and can write really good songs.”

There isn’t a particular Quiet Arch sound. Electronica, punk rock and alt-folk have had their moments on the roster. Rather, it’s a story about patience and heart and artist development. It’s about having a boss with perceptive ears and team support from Francesca and Ben. It’s about encouraging the artists to work across each other and to take audacious chances. It’s a family ethos, a cool school. Most likely, Quiet Arch is the best label on the island.

And Borders is a critical milestone. It is a measure of the huge stresses of Brexit and the responses from Irish artists. The album was literally written and recorded as Ryan Vail and Eoin O’Callaghan (Elma Orkestra) criss-crossed the border and tried to gauge the impact on themselves and their neighbours. They used binary code and classical motifs and they were gifted the voices of Moya Brennan from Clannad and the Dublin poet Stephen James Smith. It’s a work about uncertainty and at times if feels like a requiem. The multi-media live show is touring to other parts of the world marked by walls, fracture lines and intolerance. It became part of the Berlin programme for the 30th anniversary of the city’s reunification. They took it to Mexico where it resonated with Trump’s hostile rhetoric. “It’s the most punk rock thing there is,” Lyndon affirms.

And Borders is a critical milestone. It is a measure of the huge stresses of Brexit and the responses from Irish artists. The album was literally written and recorded as Ryan Vail and Eoin O’Callaghan (Elma Orkestra) criss-crossed the border and tried to gauge the impact on themselves and their neighbours. They used binary code and classical motifs and they were gifted the voices of Moya Brennan from Clannad and the Dublin poet Stephen James Smith. It’s a work about uncertainty and at times if feels like a requiem. The multi-media live show is touring to other parts of the world marked by walls, fracture lines and intolerance. It became part of the Berlin programme for the 30th anniversary of the city’s reunification. They took it to Mexico where it resonated with Trump’s hostile rhetoric. “It’s the most punk rock thing there is,” Lyndon affirms.

“They had the idea of filming the Irish border and putting in all the really beautiful spots – the drone footage, these captivating videos. And then each of those tracks had coordinates that were then linked to the videos that were the actual coordinates of the places they had been. Which were then also incorporated into the live show.

“So you had this whole puzzle. If you had the album and if you’d been to the live show and you’d watched the videos then you could find out where all these places were. Where is that island and that beach? Where is that dam? The music’s great and the BBC put them together with Moya Brennan for the TV show (Music Collaborations on BBC NI), so that got that connection together. It lent the thing a kind of gravitas. And also with Stephen James Smith and his poem, ‘My Island’.

“You had musical Irish royalty and the new young upstart poet both involved in it. That added a whole other thing to it. It was a whole package and whole concept and show. They just steamrolled themselves through. They won by sheer inventiveness. And creativity.”

Born in 1967, Lyndon’s coming-of-age music was Two Tone, The Jam and a mod revival that had been provoked by the Quadrophenia film in 1979. His uncle Jackie, a biker from Rathcoole, gave him The Who Live At Leeds and Who’s Next. When he was 18 he owned a Lambretta 250 painted maroon and cream and went on scooter runs to Morecambe and all-nighters around England. “People were dancing to northern soul. This whole subculture based on how brilliant music was. I suppose that was my first introduction to the whole 4/4 beat and dancing. That as a whole thing in itself. Which then led to a whole world of funk and rare groove and hip hop. And ultimately house music arriving on my doorstep.”

After University in Coleraine, he moved to London. He worked with Wayne Hemingway in an early version of Red or Dead in Camden Market. The city was prepped for the next major subculture and Lyndon was on it.

“I was in London in ’88 when house music landed. Bang. The second Summer of Love. Going to clubs like Shoom, The Wag and Solaris and warehouse parties. Going to see Flowered Up and The Prodigy. So many acts underneath the arches. Obviously there were pharmaceuticals involved but at the same time, you felt you were in the middle of this big paradigm shift – the world turning on its head. And the old order disappearing. Even in terms of the racial demographic, and people mixing together and what a night out meant. And like every youth culture, it thinks it’s going to change the world.

“Then in 1991 I landed back in Belfast, just as what had kicked off in London really went off here. It was the whole Art College thing, the Choice guys and Sugar Sweet – Iain McCready and David Holmes and the other lads. That would have been a very seminal scene. I have lots of great memories. Seeing Orbital in the Art College, which was pretty amazing. And Leftfield in the Ulster Hall.”

All of this fitted with the essential notions of modernism: standards rule, attention to detail, grace under pressure. He opened a shop called BLT in Rosses Court, selling Stüssy and Carhartt. Part of the former’s marketing style was to enlist underground musicians and artists into a confederate of proto-influencers – the International Stüssy Tribe. Thus, he found himself in Paris, on a Saturday night in a chic courtyard with Sean Stüssy, Goldie and sundry movers.

“And then this lady comes tottering into the courtyard with loads of wee dogs in tow. Sean’s shouting out “Susan!” They’re kissing each other and then she joins the company – Susan Sarandon.

“And then this lady comes tottering into the courtyard with loads of wee dogs in tow. Sean’s shouting out “Susan!” They’re kissing each other and then she joins the company – Susan Sarandon.

“I think, this is bonkers. I’m just this kid from Belfast and look what I’m sitting in the middle of. We ended up staying all night and flying home – getting on a flight at 6am because we didn’t want to miss any of the craic. We ended up partying with all these uber-cool people. We didn’t even unpack our bags. We just took out suitcases straight to the plane and went home.”

In the late Nineties he was running a club called Beat Suite with Marti Locke. They featured American hip hop and UK labels like Skint and Grand Central, booking DJs such as Mr Scruff and Midfield General. He was writing about dance music for the Oh Yeah website and presently he was a promoter-influencer for the Red Bull Music Academy, a moveable feast of learning, tech and international city adventures. He hung out with Motown writer-producer Leon Ware and witnessed the conscious positioning of Berlin as a music city. “They appointed a night mayor and relaxed their clubbing laws. There was an actual plan of turning Berlin into this cool city, for artists and clubbing. And it worked – a treat.”

Lyndon took regular work with Red Bull in events, setting up at festivals in a converted 1944 Dodge WC jeep that had landed at Normandy on D Day. He represented backstage at the Rolling Stones gig in Slane in 2007, playing tunes in the third tier VIP area. It was the last days of the Celtic Tiger and people were hurling the cash around.

Lyndon took regular work with Red Bull in events, setting up at festivals in a converted 1944 Dodge WC jeep that had landed at Normandy on D Day. He represented backstage at the Rolling Stones gig in Slane in 2007, playing tunes in the third tier VIP area. It was the last days of the Celtic Tiger and people were hurling the cash around.

“Anyway, I’d met all these people from around the world. I’ve got a good network. And I thought – right – I need to do something here. I was driving up to Belfast one night, listening to Zane Lowe. He was premiering a track by And So I Watch You From Afar. I was raving about them, and raving about Belfast. It was when the event, A Little Solidarity was happening (in 2008) and Oh Yeah was just kicking off. And at that point I thought right, there seems to be all this talent going on at home, there a buzz going on and I’ve got a fairly decent understanding of how all the different bits of the network work. I’ve got good connection with all the festivals in Ireland and quite a few contacts outside with the likes of Sonar in Spain. It would be good to set up a music management company.

“The big, centralised distribution centres were breaking down. It was leaving it open to someone like me, when being in the regions could be at an advantage. Because we had the same access to distribution that everyone else had. You had YouTube, SoundCloud, Spotify, iTunes. You could get a physical distributor to work with you and get your product into all the shops. And your overheads were low. Your office costs were lower. In Belfast it costs less to record, costs less to make videos, to get graphic design done. So we could easily be producing the product cheaper. But at the same time, have the same access.

“The first act to be signed to the management company was Ryan Vail. The second was UNKNWN who were fantastic. It was Chris Hannah and Gemma Dunleavy. But they broke up just when things started to go really well.”

There was payback with the Sea Legs album. Ryan Vail and Ciaran Lavery found a compatible place for synths and stories and reverie. Scraps of iPhone recordings were refashioned. Lyndon booked the pair into a converted boathouse in Portaferry for a writing session. Ciaran’s lyrics were sliced and compressed like Raymond Carver. In response, Ryan furthered the narrative with details and atmospheres.

There was payback with the Sea Legs album. Ryan Vail and Ciaran Lavery found a compatible place for synths and stories and reverie. Scraps of iPhone recordings were refashioned. Lyndon booked the pair into a converted boathouse in Portaferry for a writing session. Ciaran’s lyrics were sliced and compressed like Raymond Carver. In response, Ryan furthered the narrative with details and atmospheres.

“Sea Legs was really the start of everything. For all of us. It brought a lot of attention to both Ryan and Ciaran. It set them up well for Ciaran’s second album and Ryan’s first, which we released shortly after.

“Ryan is very methodical. It’s funny because you have those left-brain, right-brain artists. Ryan is almost like a German. Everything’s approached with this technical proficiency. He was a chemical engineer. That was his job. So it’s kinda like the least likely person but at the same time it does make sense. It’s like that classical side of things. Even though he makes things of great beauty, they’re very structured. Everything’s in its right place. That’s his tack, whereas Ciaran is very emotional, from the heart and his experiences, from his soul.

“The two of those guys, getting together and having success with that kind of collaboration as well, was the first time something like that had happened locally. Certainly, to achieve that much recognition, quite quickly. It set things up.

“And then Ciaran started to really move forward quickly with the second album, Let Bad In, which did well. He played at Willie Nelson’s ranch (in Austin, Texas) and at South by South West. With his Spotify session, he hit it out of the park and got some really mental numbers. ‘Shame’ is sitting on about 80 million. Pretty mad for a wee song written in Aghagallon. I suppose that verifies my theory of the way the word is now. You could be sitting anywhere, upload something and you can strike gold.”

At the same time, it helps to have planning and foresight, right?

“It’s addictive. Because you’re looking at everything in terms of what’s gonna happen a year from now. At least. You’re plotting and planning. The timing of everything is so important. When you’re gonna release albums, when you’re gonna tour. And also getting into the nitty-gritty of why people should care you exist as an artist. What’s the point of your music?

“Ryan’s first album was written on an inherited piano. That’s when we learnt about the strength of an album – having a great back story. If you can get the press a hook to hang it on, they’ll do half your job for you. He had inherited a piano from his wife’s grandfather, who was a fairly well-known doctor in Derry. They had shipped it over – it basically came down the Foyle on a boat. So he decided that’s what he would write this debut album on. Which then became part of the story. That did well. It got Ryan up and running.”

“Ryan’s first album was written on an inherited piano. That’s when we learnt about the strength of an album – having a great back story. If you can get the press a hook to hang it on, they’ll do half your job for you. He had inherited a piano from his wife’s grandfather, who was a fairly well-known doctor in Derry. They had shipped it over – it basically came down the Foyle on a boat. So he decided that’s what he would write this debut album on. Which then became part of the story. That did well. It got Ryan up and running.”

In August 2016 Quiet Arch took a visit from Joshua Burnside, a songwriter from Lisbane, County Down. He had a collection of songs that had come out of a trip to Latin America. There were politics, raw sentiment and Colombian rhythms. Some of the songs were mesmeric, like Biblical fever-dreams. Altogether, not a recording project that could be reduced to an easy marketing line. Lyndon almost passed up on the chance.

“I would have had loads of people coming in the door, hustling. Really too many. And Josh came in the door and I said, I’m too busy, I can’t be doing with any of that. And he said, look, can I leave you my album? I said no problem. I always tried to listen to things that people gave me, so that night I sat down in the house and listened to it and went, holy shit – is this as good as I think it is? So I listened to it again and said, this is as good as I think it is. It’s fucking amazing.

“I’m straight on the phone. When are you playing next? He said, this Friday at Stendhal. So I went to see him and he blew me away. I thought, this is Irish but it has Talking Heads in it, this is funky, this is African. This is modern. So I went straight up to him and said right, let’s go. I’m happy to work with you. I’ll put your album out, I’ll manage you. Let’s go, like.

“So I spent the next 6 months listening to the record, getting my head around it. Off I went and then February 2017 we put out the single, ‘Tunnels Pt 2’ It instantly picked up a load of 6 Music radio play. It couldn’t have gone any better. We released ‘Blood Drive’ – another load of plays. We dropped the album (Ephrata) and over the summer and things grew again

“So I spent the next 6 months listening to the record, getting my head around it. Off I went and then February 2017 we put out the single, ‘Tunnels Pt 2’ It instantly picked up a load of 6 Music radio play. It couldn’t have gone any better. We released ‘Blood Drive’ – another load of plays. We dropped the album (Ephrata) and over the summer and things grew again

“We put out a single in September and then I thought, I’ll be cute here. If he’s in for the Northern Ireland Music Prize we’ll just line up a deluxe edition of the album to be released one week after the prize. We had two sets of stickers made. One said, ‘Northern Ireland Music Prize Shortlisted Album’ and then another one, ‘Northern Ireland Music Prize Winner’. We were able to go back and then re-pitch it to Spotify and all the different places. It went onto all the biggest Spotify playlists. With this new buzz and information feed, we were able to feed it into all the 6 Music plays. It ticked all their boxes for them. All of a sudden the whole thing took off again – a second wave of life.

“Joshua’s been a brilliant artist to work with. He’s so dedicated to his art. He’s so fussy about it. He wants it all to be just so. Quite often when he brings you the stuff it’s quite challenging at the start. But I’ve got to know him. If you stick with it and you listen to it a bit. Then it’s like… wow.”

Quiet Arch and friends, 2018. Lyndon with Stevie Scullion, Aine Cronin-McCartney, Ryan Vail, Joshua Burnside, Stephen James Smith, Francesca O’Connor, Cheylene Murphy from Beauty Sleep.

Lyndon is reliably keen. He normally calls music well and anticipates a new thing. Still, he laughs about the time he first encountered the Boiler Room project near London Bridge. They were filming a Carl Craig DJ set and streaming it online. “I thought, this is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard of in my life. And then a year later, they were all millionaires.”

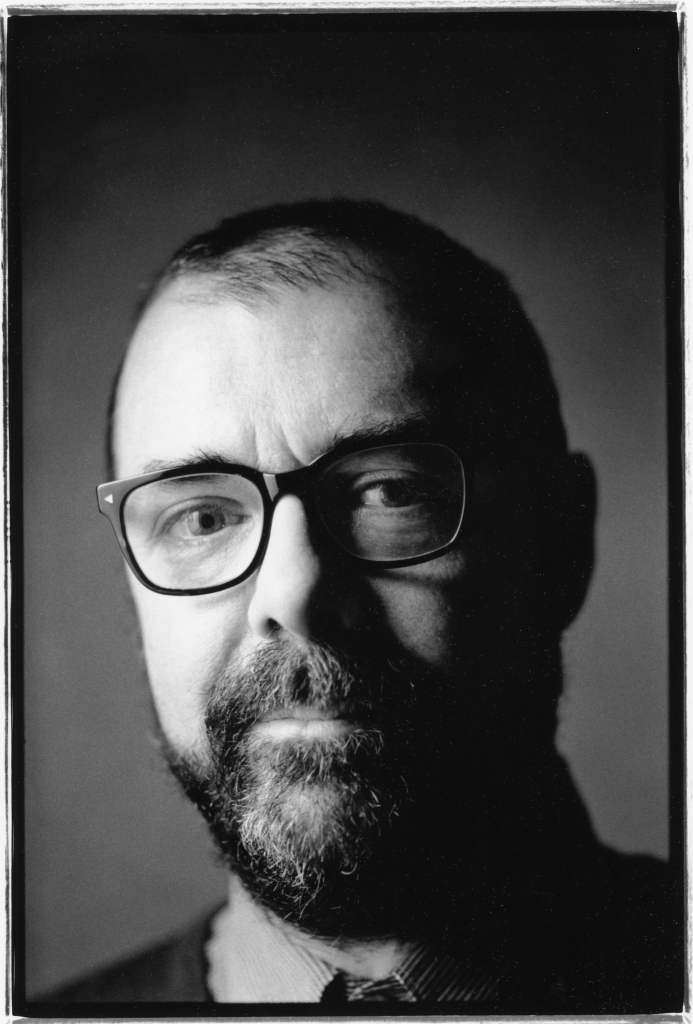

He also uses intrigue to best effect, putting out teasers and stray lines like Zen koans. The eyelids settle and the beard rustles. He has schemes and tremendous propositions. Essentially, he’s true to the boy in the backseat of the family Cortina, allowing music to give him the best steer.

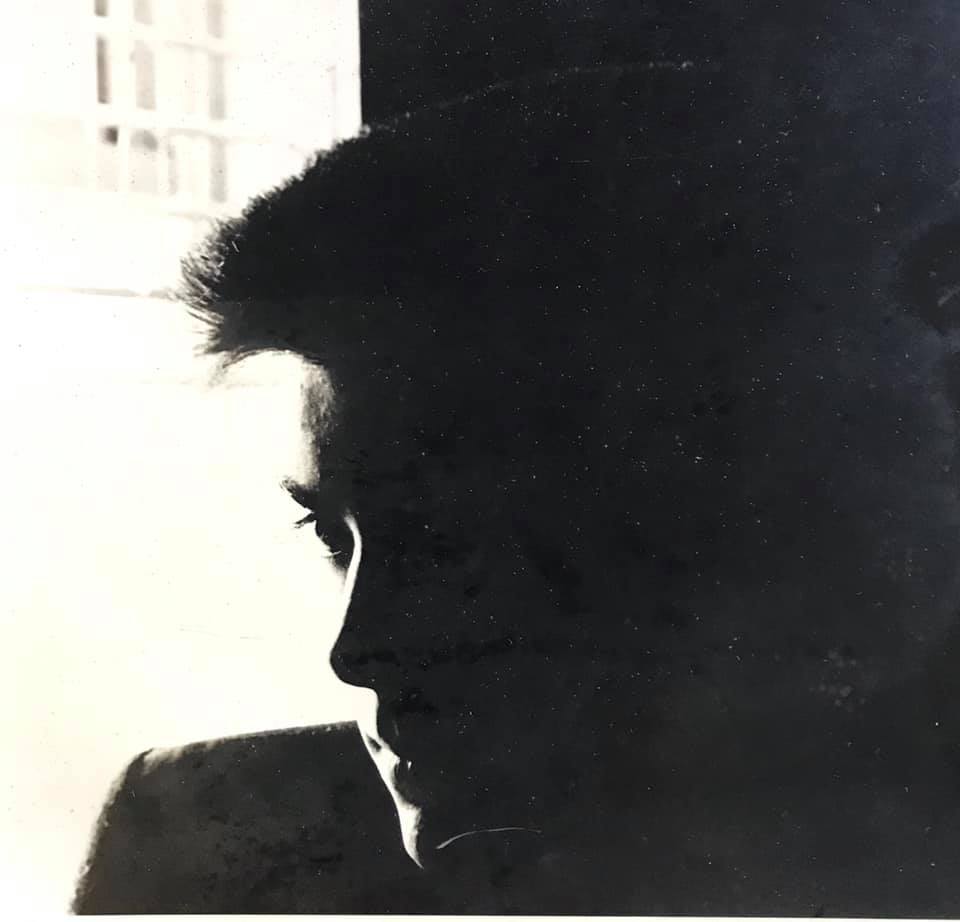

There is only one Quiet Arch release scheduled for 2020. It’s by a fresh act, as yet unpublicised. On first listen it sounds rare and exceptional. Lyndon also has an idea for some of the artwork. He wants to feature a picture of his uncle, Fred Davis, from Bandon Street on the Lower Shankill. On July 11 1973, his uncle had been to the Grand Hotel in the city centre. There was an invite to a party and the next day, his body was found in an entry in Seaforde Street. He had been strangled. Number 897 in the fatality list of the conflict. As with many losses at the time, Freddie’s family did not have a proper chance to commemorate the life, to grieve as they should. This is unfinished, emotional business.

“Freddie was homosexual and obviously it wasn’t talked about in the open in those days. Nothing made the papers. I suppose in those days it was, oh my God, this guy’s gay, let’s not mention anything. To me he’s been almost airbrushed out of history. So if there’s a photo of him on the last album, it’s just that… it’s so good… that Northern Ireland has moved on.”

Otherwise, Lyndon is resting Quiet Arch.

“Basically for now, I’m gonna park the label. I’m going to step aside from the record label to focus on my health.”

There will be a January 10 gig at The Empire in Belfast. Various Quiet Arch acts will perform and proper consideration will be due. Wonderful, sustained work. The greatest catalogue of recorded music in the city since Good Vibrations, 1978-80. Lyndon reviews the moment.

“I’m super-proud. Not to be big-headed or anything but I think that we’ve inspired an awful lot of people locally. You can actually have a music company here. You can actually employ people. You can actually do that, for a living. It doesn’t need to be a hobby, it doesn’t need to be something you do aside time from your job. That can be your job. That was always my thing – if we can just survive and pay the wages, and pay the rent and get through. It’s never been easy. But every year, you’re still there.

“And here we are, seven or eight years later. And you’ve won.”

Stuart Bailie

(Update: Lyndon Stephens died of cancer on January 10, 2020. The gig, Farewell Quiet Arch, took place that evening as planned at The Empire Music Hall, Belfast. It served as an emotional tribute to Lyndon and his pioneering work.)

Twitter

Twitter